Expert Guide to Pediatric Neurology Coding

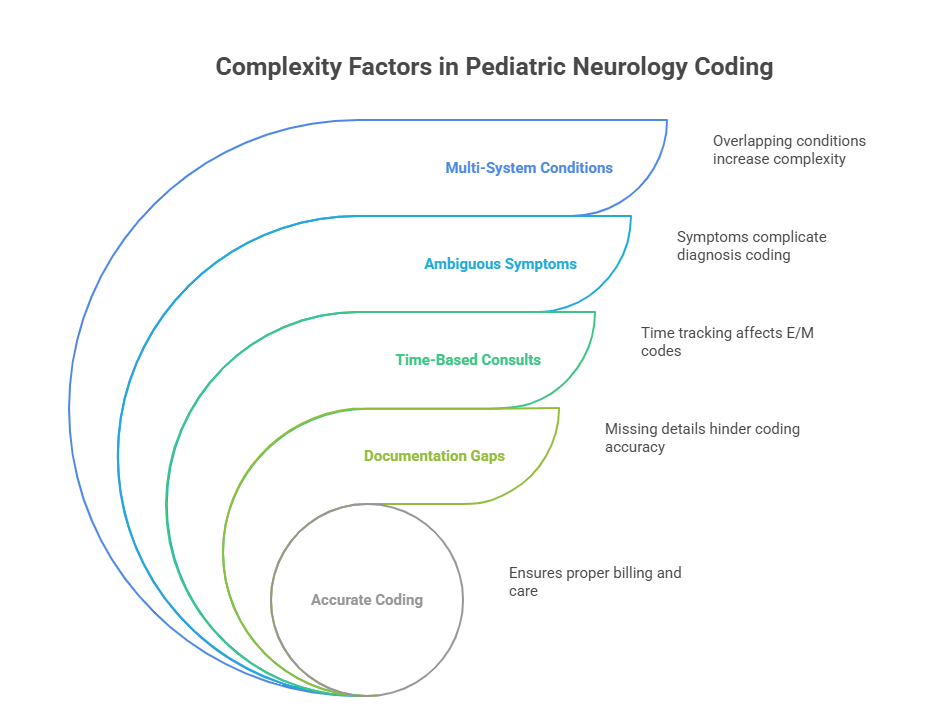

Pediatric neurology coding isn’t just a sub-specialty—it’s one of the most technically demanding sectors in the medical billing and coding field. Coders must translate complex neurological evaluations for conditions like epilepsy, cerebral palsy, or neurodevelopmental delays while factoring in age-based criteria, evolving symptoms, and ongoing growth milestones. Unlike adult neurology, pediatric cases often involve multi-system disorders, rapid diagnostic updates, and behavior-linked interpretations that make precision absolutely critical.

For Medical coders managing pediatric neurology claims, the margin for error is dangerously thin. Incorrect ICD-11 or CPT assignments not only delay reimbursement but flag compliance risks. That’s why mastering pediatric-specific nuances—like when to use time-based consult codes, how to document atypical seizures, and how modifiers apply to pediatric EEGs—is a career-defining edge. This guide breaks down the coding complexity, essential ICD/CPT codes, and documentation best practices so coders can bill confidently, avoid audits, and support high-quality care for their youngest patients.

What Makes Pediatric Neurology Coding Complex

Coding in pediatric neurology demands more than textbook knowledge. Each case is a layered intersection of age-specific neurological development, evolving symptoms, comorbid conditions, and unique care pathways. Coders must distinguish between developmental milestones and pathology, apply accurate ICD-11 diagnostic logic, and recognize the interplay between multiple systems. This complexity is amplified by frequent documentation variances and non-standardized workflows across pediatric practices.

Unlike adult neurology, where symptoms are more predictable and histories clearer, pediatric neurology coding requires inference, deep clinical understanding, and often coding for future-dated diagnoses or "rule-outs." Symptoms like ataxia, delay in walking, or language regression may suggest a broad spectrum of underlying causes, from benign disorders to progressive encephalopathies. Coders must avoid assuming the final diagnosis and instead code based on documented evidence—a distinction that affects everything from payer acceptance to audit survivability.

Age-Specific Diagnoses and Multi-System Conditions

Pediatric neurology coding often begins with the age of onset. Conditions like infantile spasms, congenital myopathies, or genetic epilepsy syndromes have different diagnostic codes depending on whether the symptoms present before age one, during early childhood, or in adolescence. Coders must not only identify the correct age grouping in ICD-11 but also match the neurology code to broader systemic implications—like metabolic or muscular involvement.

Additionally, most pediatric neurological disorders affect more than one system. A child with cerebral palsy may present with spastic quadriplegia, intellectual disabilities, and speech delays. Instead of coding only for the neurological root, high-accuracy coding reflects all clinically evaluated systems. Each of these may carry a different primary or secondary code, and the coder must sequence them in a way that supports medical necessity, treatment plans, and insurance policy parameters.

Coding also requires attention to "suspected" versus "confirmed" status in pediatric neurology. For instance, many children undergo evaluations for autism spectrum disorders, developmental dyspraxia, or motor planning issues long before a formal diagnosis. In these situations, coders should reference symptom-based codes rather than jumping ahead to a full diagnosis—ensuring compliance with payer requirements and avoiding overcoding flags.

Frequent Documentation Gaps

One of the biggest threats to accurate pediatric neurology coding is incomplete provider documentation. Pediatric neurologists may chart in shorthand, use vague descriptors like "possible delay" or "needs follow-up," or omit essential details like duration, frequency, or related symptoms. These gaps force coders into a high-risk situation where assumptions lead to denials or compliance breaches.

For example, coding for seizures without a documented type—focal vs. generalized—leads to inaccurate code selection. Similarly, developmental delays must be clearly documented as expressive, receptive, or mixed to justify the ICD-11 code used. Lack of this specificity leads to underbilling, especially when follow-up services like EEGs, neuroimaging, or speech therapy are bundled incorrectly.

To mitigate this, top coders establish feedback loops with providers, prompting clarifications or requesting addenda when documentation falls short. Coders also benefit from using coding-specific intake templates that flag missing data during pre-billing audits. Templates can remind neurologists to include seizure onset date, EEG interpretation, related conditions, and treatment initiation—elements essential for both compliance and reimbursement.

Coders in pediatric neurology must evolve beyond passive coding and into active documentation advocates, ensuring every claim reflects the full clinical picture.

Top ICD-11 Codes for Pediatric Neurology

Pediatric neurology diagnoses require exceptional ICD-11 fluency. Coders must navigate not only standard neurological codes but also age-specific subcodes, systemic overlaps, and emerging classifications introduced in ICD-11 that didn’t exist in ICD-10. With the expansion of neurological disorders and precise genetic classifications, coding precision now directly affects reimbursement, care continuity, and payer audit triggers. Below are two critical diagnostic categories that demand coder mastery.

Seizure Disorders, Developmental Delays

Seizure-related coding is among the most frequent and complex areas in pediatric neurology. ICD-11 separates generalized seizures, focal seizures, and developmental epileptic encephalopathies into detailed hierarchies that require coders to reference EEG findings, seizure frequency, and associated syndromes. For instance, a child with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (code 8E61.2) must be coded distinctly from one with benign childhood epilepsy with centrotemporal spikes.

Coding seizure activity without specifying type or age of onset is a red flag for denials. Additionally, some seizures may be coded as symptoms (e.g., “unprovoked seizure”) while others demand confirmed diagnostic assignment based on testing. This distinction is crucial in ICD-11, where provisional coding (QM0Z) is often needed pending clinical confirmation.

When it comes to developmental delays, ICD-11 no longer condenses everything into a single code. Instead, coders must classify expressive language delay (code LD20.0), receptive delay (LD21.0), or global developmental delay (LD22). This level of detail is mandatory to justify therapies such as speech pathology, occupational therapy, or neuropsychological assessments. Coders must also watch for overlapping behavioral conditions like attention deficit or autism, which may require dual coding or sequencing based on the documented primary concern.

Proper sequencing matters: if the developmental delay is a consequence of a neurological disorder (e.g., tuberous sclerosis), it should follow the primary neurological diagnosis. Failure to respect this order creates claim rejection or improper reimbursement scenarios.

Congenital Conditions and Genetic Codes

ICD-11 expands how congenital neurological disorders are coded, including syndromes with genetic markers, metabolic impacts, or structural malformations. Coders working in pediatric neurology must learn to distinguish between a structural brain anomaly (e.g., corpus callosum agenesis, code LA80.0) and a genetic syndrome like Rett Syndrome (code 8E72). Many of these now have molecular biology–linked identifiers, which should be coded when test results are documented—even if clinical symptoms are still emerging.

Another key update is the differentiation of chromosomal vs. single-gene disorders. Down syndrome, now coded under LD40, includes variants like mosaicism or translocation, each with its own code. Coders must carefully abstract from genetic test reports or neurology notes and match findings with ICD-11’s structure, which may also require post-coordination of codes to describe phenotype severity, comorbidities, or age of symptom onset.

Coders should never assume a congenital condition is neurological in origin unless specified. For example, a child with hypotonia may be coded neurologically or musculoskeletally depending on neurologist documentation. That’s why the ability to interpret provider notes precisely, and identify what ICD-11 requires versus what’s simply charted, becomes the deciding factor in compliant, audit-safe pediatric neurology coding.

Failure to reflect congenital or genetic specificity in claims leads to systemic underpayment for lifetime care and weakens clinical data used in public health surveillance.

| Condition Category | ICD-11 Code | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Generalized Epilepsy | 8E61.0 | Seizure disorder characterized by bilateral, synchronous epileptic discharges affecting both hemispheres of the brain. |

| Lennox-Gastaut Syndrome | 8E61.2 | Severe childhood epilepsy marked by multiple seizure types, intellectual disability, and slow spike-wave EEG patterns. |

| Focal Seizure with Impaired Awareness | 8E60.1 | Seizures originating in one area of the brain, accompanied by loss of consciousness or altered awareness. |

| Global Developmental Delay | LD22 | Delayed development across multiple domains such as motor, speech, cognition, and social skills without a specific cause. |

| Expressive Language Delay | LD20.0 | Difficulty in verbal expression while receptive language and non-verbal communication remain intact. |

| Receptive Language Delay | LD21.0 | Difficulty understanding spoken language, often resulting in communication and behavioral challenges. |

| Rett Syndrome | 8E72 | Neurodevelopmental disorder primarily affecting girls, involving regression in motor and cognitive skills, linked to MECP2 mutation. |

| Congenital Brain Malformation (Agenesis of Corpus Callosum) | LA80.0 | Partial or complete absence of the corpus callosum, often associated with developmental delay and seizures. |

| Neonatal Seizures | 8E70 | Seizures occurring within the first 28 days of life, often due to hypoxic injury, metabolic disorders, or congenital anomalies. |

CPT Codes for Procedures and Consults

In pediatric neurology, Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) coding isn’t just about capturing visits—it’s about translating complex evaluations, diagnostics, and multi-step consultations into precise, billable codes. The challenge lies in capturing age-adjusted assessments, EEG interpretations, developmental screenings, and multidisciplinary consults while using the appropriate modifiers and visit-level distinctions. Coders must work from comprehensive chart documentation and apply CPT definitions based on time, complexity, and medical necessity, not assumptions.

Unlike adult neurology, where follow-ups and imaging tend to follow predictable patterns, pediatric neurology is driven by growth-based timelines, interdisciplinary referrals, and high variability in encounter types. Understanding what to code—and when—is essential for accurate billing and sustainable reimbursement.

EEG, Imaging, and Follow-Up Visits

Electroencephalography (EEG) codes in pediatrics are more nuanced than they appear. Routine EEGs (95816), video EEG monitoring (95951), and extended ambulatory EEGs (95953) each require precise documentation on duration, technical component, and interpretation. Pediatric patients may need sedation or monitoring by multiple specialists—requiring coders to differentiate between professional and technical components using global vs. split billing logic.

When coding imaging, brain MRIs (70551–70553) often appear alongside consults and EEGs. However, imaging may be ordered for different reasons—seizure workups, developmental delay evaluation, or hydrocephalus monitoring. Coders must ensure the ICD code justifies the imaging modality, especially if payer guidelines require prior authorization or proof of failed conservative management. For example, coding a head MRI with “delayed milestones” without linking to a neurologically coded diagnosis often triggers denials.

Pediatric follow-up visits are equally specialized. CPT codes 99212–99215 apply to office visits, but documentation must support history, exam, and medical decision-making levels. In many pediatric neurology practices, time-based coding is more appropriate due to extended counseling, care coordination, or parental involvement. Coders must confirm that total face-to-face time is documented—and that time spent coordinating care is clearly noted if used to justify higher-level codes.

Modifier Use in Pediatric Neurology

Modifiers are essential for correct CPT interpretation in pediatric neurology. They clarify service details, avoid bundling issues, and protect claims from downcoding. However, misuse or omission of modifiers leads to immediate payment delays or pre-payment review flags—particularly with Medicare or Medicaid claims.

Modifier 25 (significant, separately identifiable E/M service) is frequently used when a neurologist performs an EEG or orders imaging during the same visit as a comprehensive consult. Coders must confirm that the E/M note is independently documented and not simply tied to the procedure.

Modifier 59 is critical when billing two distinct diagnostic services—such as a neuropsychological test and a motor coordination assessment—on the same day. Coders must ensure the services are not overlapping in scope or time. Documentation should explicitly state separate anatomical sites or clinical justifications.

In pediatric practices, Modifier 52 (reduced services) is often relevant. For example, if a child’s EEG is discontinued early due to behavioral distress, the neurologist may report a reduced version of the procedure. Coders must confirm that the report reflects time-based adjustments and supports the reduced billing.

Lastly, coders should understand payer-specific modifier combinations—some state Medicaid programs reject multiple modifiers unless sequenced exactly as per payer logic. Staying updated on these nuances ensures clean claims and optimized pediatric neurology reimbursements.

| Procedure Type | CPT Code(s) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Routine EEG (20–40 minutes) | 95816 | Standard electroencephalogram with interpretation and report; used to assess seizure activity, typically without video. |

| Extended EEG (Over 40 minutes) | 95819 | Longer EEG monitoring session often used in pediatric settings to capture irregular seizure activity or evaluate behavioral episodes. |

| Video EEG Monitoring | 95951 | Simultaneous EEG recording with video monitoring; commonly used for complex epilepsy diagnosis and surgical evaluation. |

| Ambulatory EEG | 95953 | Portable EEG performed over 24–72 hours, recorded outside a clinical setting; useful for capturing rare or sleep-related seizures. |

| Sleep-Deprived EEG | 95827 | EEG performed after sleep deprivation to enhance detection of epileptiform activity; especially useful in pediatric patients with normal routine EEGs. |

| Brain MRI without Contrast | 70551 | Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the brain without contrast, often used for evaluating structural abnormalities or developmental delay. |

| Comprehensive New Patient Consult | 99204, 99205 | Office or outpatient visit with moderate-to-high complexity medical decision-making, typically requiring 45–60+ minutes of face-to-face time. |

| Established Patient Follow-Up | 99213, 99214, 99215 | Return visits for ongoing management of neurological conditions; billed based on medical decision-making or total time spent. |

| Neuropsychological Testing by Physician | 96116 | Assessment of thinking, reasoning, and behavior—frequently ordered for pediatric patients with developmental or seizure-related cognitive concerns. |

Auditing and Compliance Risks

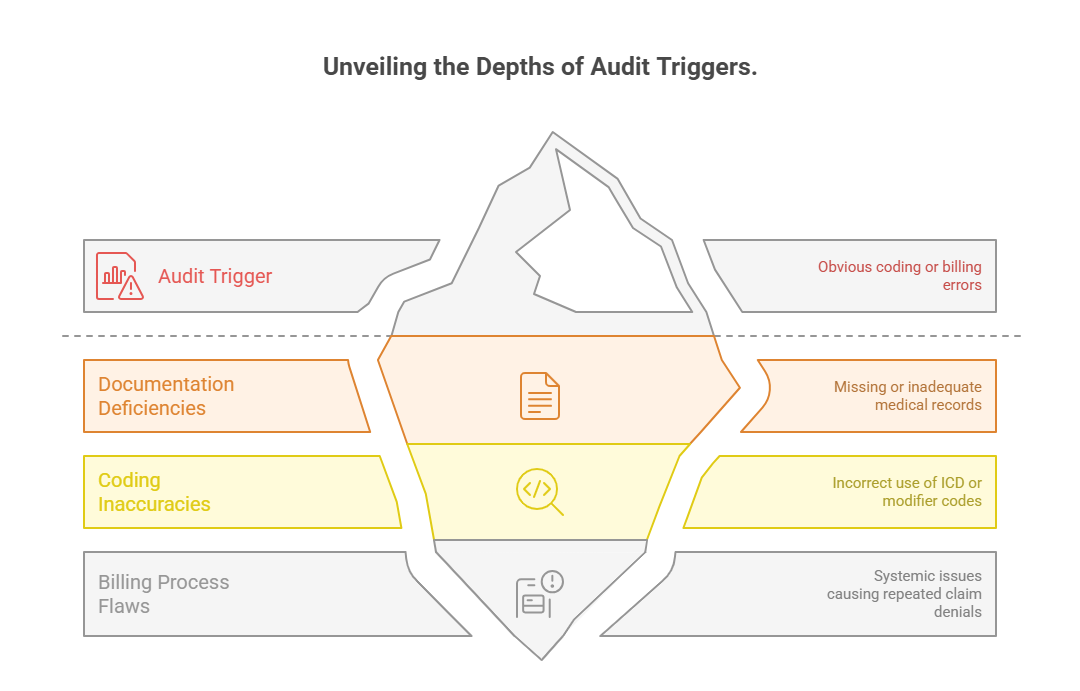

Pediatric neurology claims are frequent audit targets due to the complexity of care, time-based coding, and high-reimbursement procedures like EEGs and imaging. Even small documentation oversights—such as missing seizure type, non-specific developmental diagnoses, or unsupported time-based visits—can trigger payer reviews, denials, and clawbacks. Coders working in this specialty must maintain rigorous audit readiness, applying not just coding knowledge but also documentation compliance strategy.

Payers increasingly use AI to flag outlier claims. If a pediatric neurologist consistently bills higher-level E/M services or frequently uses Modifier 25, the practice may be placed under enhanced scrutiny—even if the care was clinically justified. That’s why coders must not only apply the correct CPT and ICD codes but also validate the narrative against coding-level requirements to prevent revenue risk.

Common Denials and Underbilling Patterns

The most common denials in pediatric neurology coding involve insufficient documentation or inappropriate code combinations. For example, submitting a claim for a follow-up consult with a high-level E/M code without evidence of complex decision-making or prolonged time results in automatic downcoding or rejection.

Another common issue is underbilling due to generic ICD codes. Using a vague code like “developmental delay, unspecified” (LD22.Z) instead of a specific language or cognitive delay leads to denials for therapy services and triggers compliance flags. Similarly, coding EEGs without linking the test to medically necessary seizure classification or prior failed treatments risks denial—even if the test was clinically warranted.

Many practices also lose revenue due to modifier omissions. A missing Modifier 25 on a same-day EEG and consult means one of the services gets bundled or rejected. Even more costly is the use of Modifier 59 without adequate justification, leading to post-payment audits.

How to Prepare for Payer Scrutiny

Audit readiness starts with real-time documentation validation. Coders should use checklists during coding to ensure all billing elements are present: specific diagnosis codes, accurate CPT descriptions, time-based documentation (if applicable), and clear procedural notes.

A strong internal audit process should include quarterly reviews of high-dollar claims, especially those involving EEGs, genetic testing, or prolonged consults. Claims that deviate from payer norms—such as consistent use of 99215—should be flagged for review, even if they haven’t been denied yet.

Coders must also stay updated on payer policy changes. Some payers now require additional documentation for certain pediatric epilepsy syndromes, especially when linked to long-term therapy or genetic consultations. Coders who align their coding practice with payer-specific LCDs or NCDs help reduce denials and audit risk.

Finally, establishing coder–provider collaboration is essential. When neurologists are trained on documentation gaps that trigger audits, practices reduce risk, ensure compliance, and build a culture of coding integrity that protects long-term financial stability.

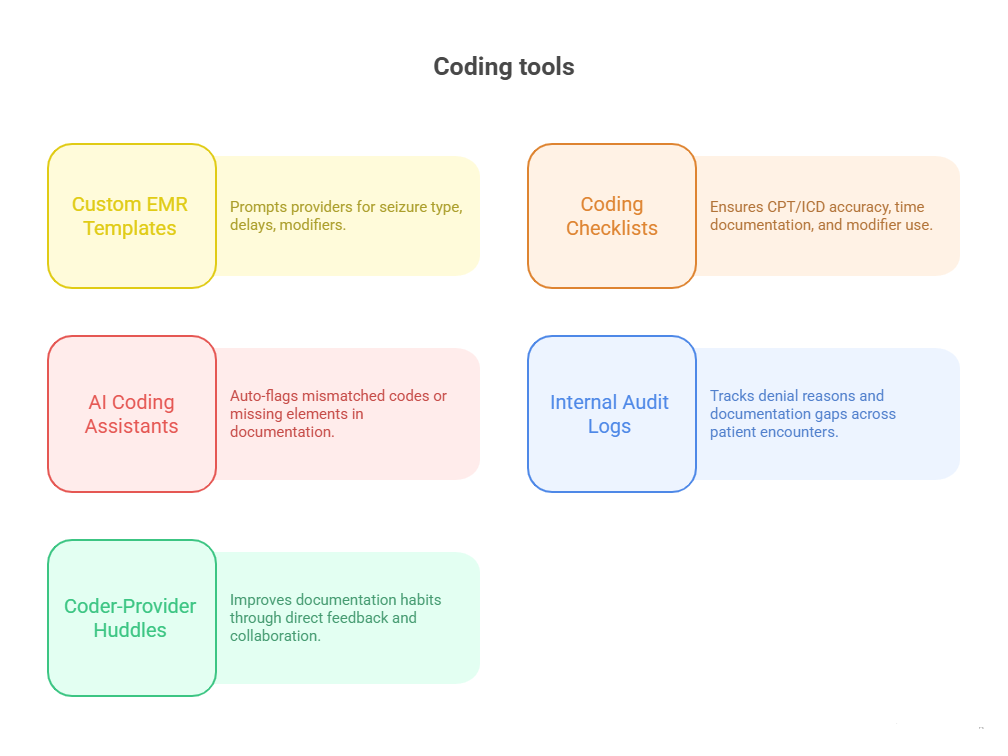

Improving Accuracy with Templates and Tools

Accuracy in pediatric neurology coding hinges not just on coder expertise but on the systems and tools used to capture clinical data. Even skilled coders fall short when documentation lacks specificity, misses modifiers, or doesn’t align with coding logic. EMR optimization, customized templates, and provider-driven checklists drastically improve the precision, speed, and audit resilience of coding operations. Coders must work in lockstep with providers to create streamlined digital workflows that embed coding logic into clinical charting habits.

EMR Shortcuts and Coding Checklists

Custom EMR templates for pediatric neurology reduce error rates by up to 40% in high-volume practices. These templates prompt clinicians to enter specific diagnostic details, such as seizure onset date, frequency, type, and EEG correlation. They also guide neurologists to clarify developmental delays (expressive vs. global) and note comorbid symptoms or suspected syndromes—details often missed in free-text charting.

Coders should advocate for dropdowns or checkbox-driven fields for:

Seizure classification (focal/generalized/mixed)

Diagnostic certainty level (suspected, confirmed, rule-out)

Genetic test results and referral notes

Time spent in consults and coordination (for time-based billing)

Alongside EMR improvements, coding checklists play a vital role. Checklists ensure nothing critical is overlooked, such as:

Inclusion of ICD-11 specificity

Documentation of medical necessity for imaging

Proper use of CPT modifiers (e.g., 25, 59, 52)

Alignment of documentation with billed time or complexity

These tools don't just prevent denials—they also accelerate coder throughput, reduce provider back-and-forth, and keep the practice compliant with payer audit protocols.

Collaboration with Providers

Coders in pediatric neurology must function as clinical translators and compliance educators, not just code extractors. Providers often don’t realize how small documentation lapses—like omitting seizure type or visit time—can result in undercoding, bundled services, or post-payment audits. Creating an open feedback channel allows coders to regularly share:

Missed documentation elements from prior notes

Denial trends linked to charting gaps

Recommendations for coding-optimized phrasing

Regular 1-on-1 sessions or quick daily huddles between coders and pediatric neurologists help build mutual understanding. For example, explaining how “prolonged follow-up due to parent counseling” supports a higher E/M level prompts better documentation behavior. Coders can also train staff on use of codable language, like “medically necessary EEG ordered due to spike activity on recent episode” instead of vague terms like “monitoring EEG.”

These partnerships reduce claims rework, limit payer pushback, and support clean revenue cycle operations. Ultimately, tools are only as effective as the coder–provider synergy behind them.

Strengthen Your Coding Career with AMBCI

Pediatric neurology is one of the most demanding specialties in medical billing and coding, and coders who master its complexities are in short supply. The AMBCI Medical Billing and Coding Certification gives professionals the specialized training, system fluency, and regulatory readiness needed to excel in this niche. From deciphering EEG patterns to understanding genetic disorder documentation, AMBCI’s curriculum prepares coders for real-world pediatric neurology billing with confidence and precision.

This isn’t a generic billing course. AMBCI has tailored its program for advanced coding applications, including pediatric specialties, payer compliance, and modifier application. Through 200+ advanced modules, learners build the ability to handle seizure classifications, congenital code hierarchies, multi-system documentation, and CPT audit risk zones—all of which are common in pediatric neurology.

More importantly, AMBCI certifies coders with real-world fluency. It trains professionals to:

Read neurology consults like a compliance auditor

Apply modifiers based on CMS guidelines

Use ICD-11 with pediatric coding specificity

Prevent underbilling across developmental cases

As coding teams are increasingly tasked with reducing claim edits and increasing clean submission rates, certified coders from AMBCI stand out for their specialized training and coding precision in pediatric subspecialties.

Pediatric-Focused Coding Lessons Included

One of the standout features of the AMBCI Medical Billing and Coding Certification is its dedicated pediatric neurology unit. This isn’t just theory—it’s training based on how pediatric cases actually unfold in practice, including incomplete documentation, rare syndromes, and the nuances of EEG billing in underage patients.

The pediatric neurology module walks you through:

Assigning ICD-11 codes for genetic and developmental conditions

Handling ambiguous diagnoses in infants and toddlers

CPT selection for multi-component visits (consult + imaging + testing)

Real scenarios of seizures, cerebral palsy, and neurodevelopmental assessments

You’ll also master modifier logic specifically for pediatrics, where procedures are frequently adjusted, repeated, or reduced due to patient behavior or sedation limits. The course uses real chart examples from pediatric neurologists, so you see exactly how to navigate clinical ambiguity without risking overcoding or noncompliance.

This training goes far beyond textbooks—it's built for coders who want to lead coding accuracy and compliance efforts within pediatric practices, hospitals, or specialty clinics.

Enroll Now and Elevate Your Pediatric Coding Expertise

Ready to step into one of the most in-demand coding specialties in healthcare? The AMBCI Medical Billing and Coding Certification offers a direct path to mastering pediatric neurology coding, giving you the edge to bill with confidence, reduce denials, and accelerate your career in a niche where precision equals opportunity.

You’ll get:

Lifetime access to 200+ advanced billing lessons

Dedicated ICD-11 and CPT pediatric neurology modules

Training aligned with payer-specific compliance standards

Exam prep and resume-ready certification in as little as 7 weeks

Whether you're just starting or upskilling into a specialized niche, AMBCI helps you become a coder hiring managers trust for high-stakes specialties like pediatric neurology.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Pediatric neurology coders frequently work with conditions such as epilepsy, developmental delays, cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorders, and congenital malformations of the brain or spine. These cases often involve overlapping symptoms like language regression, hypotonia, or motor coordination issues. Coders must be highly specific with ICD-11 codes—distinguishing between focal and generalized seizures or expressive vs. receptive language delays—to support accurate treatment authorization and reduce payer denials. Comorbidities like ADHD, intellectual disabilities, or genetic syndromes (e.g., Rett or Fragile X) often require dual coding with correct sequencing. Each diagnosis must align with clinical documentation, especially in multi-specialty practices where neuro, psych, and rehab codes intersect in a single patient encounter.

-

ICD-11 brings far greater specificity to pediatric neurology than ICD-10. Many diagnoses now include details like age of onset, molecular subtype, and severity gradation. For example, epilepsy syndromes are coded not just by seizure type but by underlying genetic or structural origin. Developmental disorders are no longer lumped together; ICD-11 distinguishes expressive, receptive, and global delays, which affects therapy approvals. The classification system also introduces post-coordination, allowing coders to add dimensions like comorbid behavioral conditions or symptom triggers. This enhances clinical accuracy but requires advanced training. Without this knowledge, coders risk miscoding rare or evolving neurological conditions, leading to underpayment or compliance violations.

-

The most commonly used CPT codes for pediatric EEGs include 95816 for routine EEG (20–40 minutes), 95819 for extended EEG (>40 minutes), and 95951 for video EEG monitoring. Pediatric cases often require 95827 (EEG with sleep deprivation) or 95953 (ambulatory EEG with computer analysis). Billing accurately requires splitting technical and professional components using modifiers -26 and -TC when services are performed across locations. Coders must also document sedation use, incomplete studies, or failed tests—especially if using Modifier 52 (reduced services). Pediatric EEG billing often intersects with high-level E/M codes or neurological consults, requiring Modifier 25 to avoid denials for bundled services during the same visit.

-

Modifier 25 indicates a significant, separately identifiable E/M service provided on the same day as another procedure. In pediatric neurology, it’s commonly applied when a neurologist performs a detailed consult in addition to procedures like EEGs, MRIs, or developmental testing. For Modifier 25 to be valid, documentation must clearly show the E/M service was medically necessary and not solely for performing the procedure. Coders should verify that history, exam, and medical decision-making elements meet CPT criteria for a distinct visit. Improper or missing use of Modifier 25 leads to denials or bundling issues, especially with Medicaid or commercial payers that strictly audit modifier justification.

-

To avoid denials, coders must select specific ICD-11 codes—not general terms like “developmental delay.” For example, use LD20.0 for expressive language delay or LD21.0 for receptive delay based on provider documentation. Coders should ensure that delays are supported by evaluations such as speech/language assessments, neurodevelopmental reports, or therapy referrals. Payers often deny codes lacking clear documentation of onset, severity, and associated conditions (e.g., autism or seizure disorders). If the diagnosis is still under evaluation, symptom codes may be more appropriate. Using unspecified codes too frequently raises audit risk, reduces payment, and may limit access to therapies unless medical necessity is well documented.

-

Yes. Pediatric neurology claims are frequent audit targets due to high-cost services, modifier usage, and coding complexity. Procedures like EEGs, prolonged consults, and genetic evaluations often trigger payer scrutiny, especially when billed with high-level E/M codes. Coders must document time, medical necessity, and specific diagnoses to justify every claim. Improper modifier usage (like missing Modifier 25 or incorrect use of Modifier 59) also flags claims for review. Additionally, repeated use of broad codes (e.g., “global developmental delay”) raises compliance concerns. To reduce risk, coders should implement internal audits, payer policy tracking, and regular provider education on documentation standards.

-

Top tools include custom EMR templates, coding checklists, and real-time audit prompts. Templates guide providers to document seizure types, developmental specifics, and time spent—preventing undercoding or vague notes. Checklists ensure that required elements like modifier usage, diagnosis justification, and CPT alignment are consistently applied. Many coders also use AI-powered coding assistants or payer rule databases to check code combinations before claim submission. High-performing practices rely on tools that flag mismatches between documentation and billed codes, especially for time-based services or bundled encounters. These systems reduce rework, improve clean claim rates, and support long-term compliance across pediatric neurology workflows.

Final Thoughts

Pediatric neurology coding isn’t just about applying codes—it’s about interpreting complex clinical narratives, identifying multisystem pediatric disorders, and translating evolving diagnoses into accurate, audit-ready claims. From seizure classifications to genetic syndromes, coders must bring not only technical skill but also clinical insight and compliance strategy to every case.

With ICD-11 demanding greater specificity and CPT logic increasingly tied to documentation precision, coders who master pediatric neurology become invaluable assets in today’s healthcare revenue cycle. The margin for error is thin—but the opportunity for career growth is immense.

Whether you’re refining your expertise or entering the field, investing in the right training—like the AMBCI Medical Billing and Coding Certification—can equip you with the tools to code with confidence, support providers more effectively, and lead in one of the most impactful specialties in medical coding.