Comprehensive Guide to Medical Coding in Complex Trauma Cases

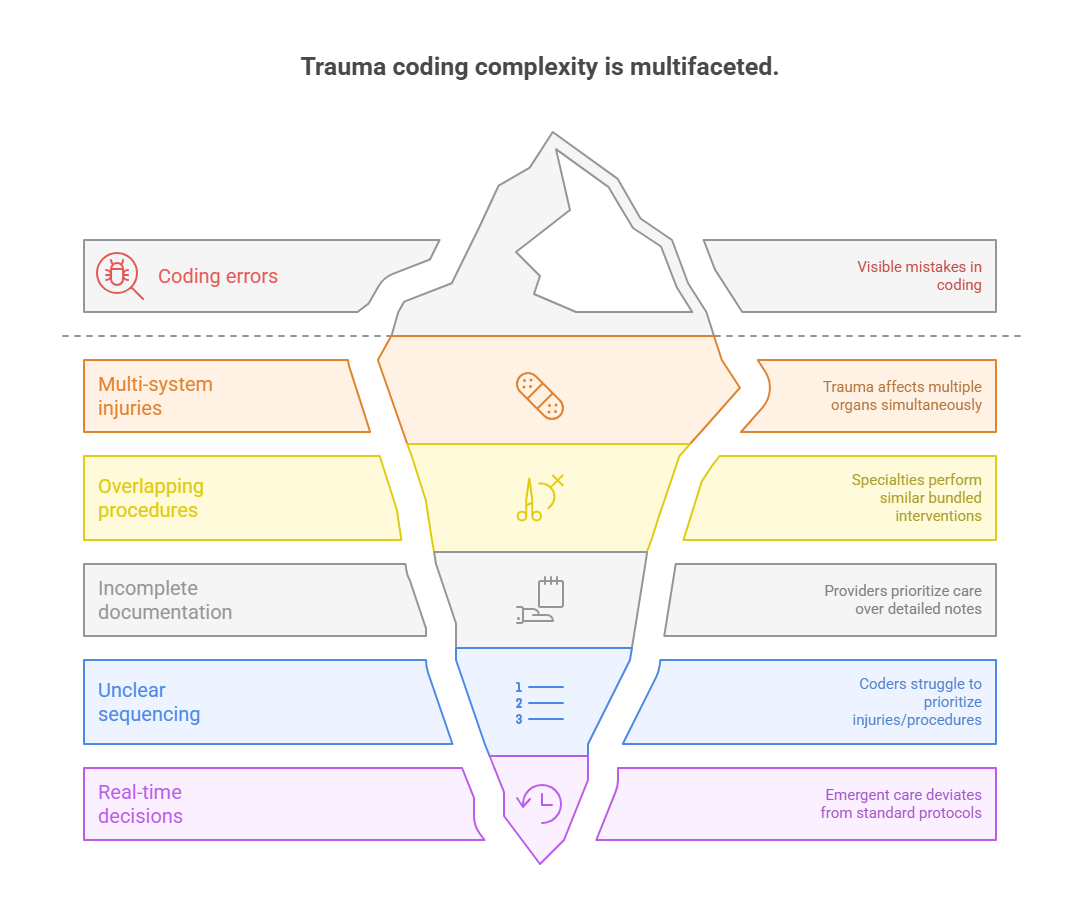

Accurate medical coding in complex trauma cases isn't just difficult—it’s a high-stakes task that directly affects claim approvals, audit risk, and hospital revenue. Trauma cases typically involve multiple body systems, emergency surgical interventions, and simultaneous diagnoses, making them far more intricate than routine inpatient or outpatient encounters. Coders must rapidly decode chaotic, time-pressured documentation while adhering to precise coding standards.

For healthcare organizations, even a single missed code or misapplied modifier in trauma documentation can result in thousands of dollars in lost revenue, claim denials, or compliance violations. This guide breaks down every layer of trauma coding—from understanding multi-system injury logic to applying modifiers under surgical bundling rules.

What Makes Trauma Coding Complex?

Trauma coding goes beyond standard procedural documentation—it’s a high-pressure interpretive task that requires coders to extract complete narratives from fragmented records. In many trauma cases, physicians focus on stabilization, not documentation, which leaves coders with ambiguous or incomplete notes to work from. Add in the urgency of life-saving interventions and the overlap of multiple injuries, and you have a perfect storm for coding errors.

Even highly experienced coders can struggle to determine primary diagnoses, appropriate sequencing, or modifier usage when the chart is unclear or when different departments document overlapping interventions. What makes trauma coding truly complex isn’t just volume—it’s the variable structure of each case, driven by emergent decision-making and evolving clinical data.

Multi-System Injuries and Procedure Overlaps

Complex trauma cases typically involve injuries across two or more body systems, such as orthopedic damage paired with internal organ trauma. This forces coders to navigate ICD-10-CM coding hierarchies, cross-reference procedural timelines, and determine if interventions were part of bundled services or distinct reportable events.

For example, when a patient presents with a fractured pelvis and internal bleeding, surgical teams may conduct orthopedic fixation and abdominal laparotomy within the same operative session. Coders must decide whether to apply modifier 59 to signal distinct procedural work or follow NCCI edits that instruct otherwise. This challenge is further complicated by lack of clarity on timing—if two procedures occurred back-to-back in the same suite, was one incidental?

Additionally, duplicative procedure codes from different specialists—orthopedists, trauma surgeons, and radiologists—can trigger denials if not sequenced and modified correctly. Each department’s documentation may describe overlapping or even conflicting procedures. Coders are expected to synthesize this into a clean, compliant claim.

Emergency Care Timing & Documentation Gaps

In trauma cases, documentation often lags behind clinical action, especially in ER-to-OR transitions. Physicians may update notes retroactively, or not at all, particularly for second or third procedures performed in a chain reaction. This delay creates coding blind spots, especially when timestamps are vague or missing entirely.

Timing matters immensely. If a critical care service (CPT 99291) is coded but overlaps with a surgical event or anesthesia billing, coders must evaluate the time thresholds and determine if separate reimbursement is justified. A 45-minute bedside resuscitation may sound billable, but if it leads directly into surgery without a proper break or clear documentation of separate services, it may be denied.

Coders must also account for evolving diagnoses. A head injury that initially appears minor might later be classified as a traumatic brain injury (TBI) after CT scan results. Coders need to revise diagnoses and sequencing based on this evolving clinical picture—often without being alerted by providers.

ICD-10 Guidelines for Trauma Cases

Applying ICD-10-CM in trauma coding requires a deep understanding of both structural logic and clinical nuance. Trauma doesn’t present in linear form—so coders must navigate combination codes, injury hierarchies, encounter classifications, and external cause reporting, often within the same episode of care. A misstep in sequencing or missing an external cause code can result in DRG misassignment, payer rejection, or loss of valuable injury severity scoring that affects hospital reimbursement.

Because trauma patients frequently have multi-faceted and evolving conditions, coders must constantly determine the clinical significance of each injury, prioritize based on treatment rendered, and apply codes that reflect completeness, causality, and medical decision-making—all within ICD-10’s rigid structural rules.

Injury Coding Hierarchies and Combinations

ICD-10 provides specific instructions on how to report multiple injuries, but the nuance lies in recognizing which injuries take coding priority. In trauma, coders must follow these core principles:

Code the most severe injury first—even if it wasn't the one initially treated.

Combine injuries using T07 or T14.8 codes only when detailed injury sites are not specified.

Avoid coding superficial wounds (abrasions, contusions) when deeper injuries to the same site are present.

For example, if a patient has both a rib fracture and pulmonary contusion, the contusion (a more severe, function-impacting injury) should be listed first, unless surgical management indicates otherwise.

Coders must also be fluent in the use of 7th characters for trauma: “A” for active treatment, “D” for subsequent care, “S” for sequela. Incorrect use of these modifiers can lead to automated payer denials, especially for ongoing trauma follow-up visits coded with “A” instead of “D.”

In trauma coding, using combination codes can also streamline claims but requires precision. For instance, certain intracranial injuries are pre-combined with skull fractures. Reporting them separately not only violates coding rules but may misrepresent case complexity.

External Cause Codes and Place of Occurrence

Trauma coding under ICD-10 also demands coders report how and where an injury occurred—data that’s critical for both public health surveillance and payer analytics. These are not typically reimbursed codes but are required for claim completeness and compliance.

Coders must:

Use V00–Y99 for external causes: e.g., V89.2XXA for “driver injured in collision with fixed object.”

Use Y92 codes for location: e.g., Y92.250 for “injury occurred in kitchen.”

Add activity codes (Y93) if applicable: e.g., Y93.G1 for “injury while cooking.”

While these codes may seem non-essential, failing to report them can flag records as incomplete in payer systems and government trauma registries. This especially impacts trauma centers aiming for ACS Level I/II accreditation, where data reporting standards are monitored tightly.

Even more crucial: never assign an external cause code unless it's explicitly documented. Assumptions—even obvious ones like “car accident”—are never permitted in trauma coding. Always query if the mechanism or location is unclear.

CPT & Modifier Use in Trauma Procedures

Trauma coding with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) is where reimbursement risks escalate. Coders must decipher high-pressure operative notes, differentiate between bundled and separately billable procedures, and apply the right modifiers to survive payer edits and audits. The complexity arises not just from the procedures themselves but from the timing, provider specialties involved, and payer-specific rules around modifier application.

Errors in this phase result in undercoding, overcoding, or denials, especially when modifiers are misapplied or omitted. Trauma scenarios demand coders go beyond boilerplate CPT usage and instead interpret the intent and documentation context for each intervention.

Surgical Procedure Coding in Trauma Settings

In trauma, surgeries are often performed in rapid sequence, sometimes without clear sectioning in the documentation. A single note may describe a craniotomy, chest tube insertion, and exploratory laparotomy—all within a short operative window. Coders must:

Determine if procedures are bundled under NCCI edits or qualify as separate services.

Use operative reports, anesthesia records, and nursing notes to identify procedure timing and medical necessity.

Code only completed, documented procedures—not those intended or attempted.

For example, a vascular repair attempted during trauma resuscitation but abandoned midway due to hypotension should not be coded as completed unless clearly documented as such. Coders must watch for phrases like “aborted,” “converted,” or “incomplete” and adjust CPT selections accordingly.

Surgical teams may also document multiple incisions or body regions. In such cases, coders must verify if CPT codes stack correctly, or if they require modifier 51 (multiple procedures) or modifier 59 to bypass NCCI bundling.

Coders working in trauma hospitals should be trained to read across documentation types, not just surgeon dictations, to gather evidence for standalone procedural coding.

Modifier 59, 25, and Trauma Bundling Rules

Modifiers in trauma coding can determine whether a $15,000 claim is paid or denied outright. The most misunderstood in this domain are Modifier 59 (distinct procedural service) and Modifier 25 (separately identifiable E/M service).

Modifier 59 should only be used when procedures are documented as independent, occurred in distinct anatomic sites, or were clinically separate.

Example: Repairing a tibial fracture and inserting a chest tube in the same surgical episode may require Modifier 59 if documentation clearly separates the two.

Modifier 25 applies when a provider delivers a significant E/M service on the same day as a procedure. It’s valid only if the E/M work stands on its own, such as a detailed trauma evaluation prior to an unexpected surgical intervention.

Overuse of these modifiers, especially Modifier 59, is a red flag for payers and auditors. CMS has identified Modifier 59 as one of the most abused coding practices, often leading to automated denial algorithms.

To prevent rejections:

Always cross-check with NCCI edit tables before applying any modifier.

Use modifier-specific documentation phrases (e.g., “distinct procedural session,” “separate anatomical site”).

Validate through physician queries when ambiguity exists.

Coders in trauma environments must treat modifiers as precision tools, not default coding workarounds.

| Component | Description | Application in Trauma Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Modifier 59 | Used to report procedures that are distinct and not normally billed together. | Must reflect different sites or sessions (e.g., chest tube + limb fixation); overuse triggers denials. |

| Modifier 25 | Applied when a significant, separately identifiable E/M service is provided on the same day as a procedure. | Often used in trauma ED scenarios—requires complete, standalone documentation of the E/M service. |

| NCCI bundling edits | National guidelines on which CPT codes can be reported together without modifiers. | Coders must cross-check edits before submission to avoid automatic payer rejections. |

| Procedure intent clarification | Defines whether two procedures were distinct, staged, or part of a continuous effort. | Critical when determining if multiple surgical CPTs should be coded separately or bundled. |

| Timing documentation | Exact timeframes for procedures help determine code sequencing and modifier validity. | Especially important when procedures occur in the same session but for different clinical reasons. |

Real-World Case Studies: What Coders Got Wrong

Understanding the real cost of trauma coding errors requires examining how mistakes play out in actual claims. These aren’t just technical errors—they often lead to full claim denials, payment downgrades, audits, or financial clawbacks. Coders navigating trauma cases must learn from these outcomes and understand how small documentation gaps or modifier missteps can snowball into six-figure losses for healthcare systems.

This section presents two instructive case studies: one where coding errors led to denials, and one showing how proactive documentation queries could have changed the result entirely.

Denied Claims Examples

Case 1: Modifier Misuse in Emergency Ortho Case

An orthopedic trauma surgeon performed open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) for a distal femur fracture and also removed a previously implanted rod from the tibia. The coder submitted CPT codes 27507 (ORIF) and 20680 (implant removal) on the same claim with Modifier 59 applied to the removal.

Problem:

The removal procedure lacked clear anatomic separation in the operative report, and the payer flagged Modifier 59 as incorrectly applied. The entire claim was denied, citing improper unbundling.

Lesson:

Modifier 59 must be supported by explicit documentation distinguishing procedures—different incisions, body parts, or clinical intents—not just separate CPTs. Coders should have queried the physician or attached additional notes.

Case 2: E/M and Procedure Conflict

In an emergency trauma admission, a physician conducted a full-level trauma evaluation and also performed a laceration repair. The coder billed 99285 (high-level ED E/M) and 12034 (intermediate repair) with Modifier 25.

Problem:

Payer audits found no distinct E/M documentation—the history and exam were focused entirely on the wound. Result: downcoded E/M and partial denial.

Lesson:

Modifier 25 demands that the E/M portion be separately and fully documented, with distinct reasoning and medical decision-making beyond the procedure.

How Proper Documentation Could Have Prevented Issues

The missing link in both cases? Documentation strategy. Had the surgeons or emergency physicians clarified the reason for the second procedure, distinct body locations, or time stamps, coders would have had grounds to support their coding logic.

Preventive best practices include:

Pre-op and post-op summaries clearly outlining procedural intent.

Use of terms like "unrelated procedure" or "distinct anatomical location" in the operative narrative.

Progress notes or ED notes that separately support E/M services without relying on procedure documentation.

In high-volume trauma centers, failing to proactively document these distinctions leads to chronic underpayment and higher denial rates. Institutions that train physicians in coding-conscious documentation consistently outperform those that rely solely on coder back-end adjustments.

The takeaway: coders cannot code what isn’t documented, and what is documented must be specific, intentional, and audit-ready.

Best Practices for Accurate Trauma Coding

Precision in trauma coding hinges not just on technical knowledge—but on proactive collaboration, real-time clarification, and consistent use of reference tools. Even the most experienced coders will encounter cases where documentation conflicts, overlaps, or falls short. What separates a high-performing trauma coder from an average one is their ability to fill the gaps ethically, without assumptions, using validated best practices that protect revenue and compliance.

Let’s explore two core strategies that make a measurable difference in coding accuracy across complex trauma cases.

Querying Physicians

In trauma environments, coders must treat physician queries as standard workflow, not exceptional events. It’s not about questioning medical judgment—it’s about getting the documentation to reflect the clinical reality coders are being asked to report.

Best practices for trauma-focused queries include:

Timing: Don’t delay. Initiate queries within 24 hours of chart review to align with physician recall and avoid claim delays.

Specificity: Ask targeted questions. Instead of "Can you clarify the injury site?" ask, “Was the open fracture of the tibia or fibula, and was it Gustilo type I, II, or III?”

Compliance format: Use non-leading query language and retain query responses in the EHR for audit visibility.

For example, if documentation mentions “leg fracture” but an X-ray reveals both tibia and fibula fractures, coders must clarify which bone(s) were treated and if an open wound was involved. Failing to do so could cause miscoding under ICD-10’s specific S82.x fracture classification hierarchy.

Queries are especially vital for determining:

Injury severity (e.g., minor vs. major trauma)

Use of general vs. regional anesthesia

Distinction between planned vs. emergent procedures

Coders working in trauma must be comfortable initiating multiple queries per encounter when needed—and ensure those responses alter the claim before submission.

Use of Coding Reference Tools

No trauma coder should operate on memory alone. The complexity of emergent interventions and bundled CPT edits makes real-time referencing essential. Coders should maintain a curated suite of tools and use them before finalizing claims, especially in trauma-heavy institutions.

Recommended tools include:

ICD-10-CM Official Guidelines (updated yearly)

AAPC/NCCI Procedure-to-Procedure Edit Checkers

CPT Assistant and Coding Clinic references for trauma-specific clarifications

Clinical Decision Support (CDS) tools embedded in the EHR for flagging missing elements

Reference tools should be actively used to:

Validate modifier use against payer-specific guidelines.

Confirm whether CPT codes are mutually exclusive or require override modifiers.

Identify missing external cause codes or seventh characters.

Experienced trauma coders also build customized quick-reference lists for frequently encountered injuries in their facility (e.g., gunshot wounds, multiple fractures, blunt abdominal trauma) with pre-vetted code groupings and documentation checklists.

By embedding reference tools into daily practice—and treating queries as part of coding, not an afterthought—trauma coders elevate their accuracy, reduce denials, and become essential contributors to revenue integrity.

| Best Practice | Purpose | Impact on Trauma Coding |

|---|---|---|

| Timely physician queries | Clarifies vague documentation such as injury specifics, procedure intent, or laterality. | Reduces denials, ensures ICD-10 codes reflect clinical severity, and enables modifier accuracy. |

| Use of non-leading language | Maintains compliance by avoiding suggestive or assumptive phrasing in queries. | Protects coders and organizations during audits; preserves integrity of the record. |

| Real-time reference checks | Validates code selections against the latest ICD-10, CPT, and NCCI guidelines. | Prevents overcoding, unbundling, and missed revenue opportunities. |

| Cross-documentation review | Compares surgeon, ED, anesthesia, and nursing notes for full case context. | Ensures accurate sequencing and detection of procedures not noted in op reports. |

| Specialty-specific quick-reference lists | Pre-built, pre-validated code combinations for common trauma patterns. | Speeds up workflow and minimizes variation across coders handling similar cases. |

How AMBCI’s Advanced Coding Course Covers Complex Cases

Coders dealing with trauma scenarios require more than textbook instruction—they need immersive, scenario-based training that mirrors real hospital complexities, surgical urgency, and documentation pitfalls. The AMBCI Advanced Medical Billing and Coding Certification addresses this need by going beyond basics and diving deep into high-risk, multi-layered trauma coding cases. Every module is structured to build applied expertise, not just theoretical understanding.

Coders emerging from this course are equipped to handle ICD-10, CPT, and modifier combinations with confidence—even under extreme clinical ambiguity or documentation gaps.

Trauma-Based Simulation Cases

One of the most valuable components of the AMBCI certification is its trauma simulation module series. These aren’t generic charts—they’re based on real anonymized trauma cases, complete with ER intake notes, operative reports, radiology findings, and incomplete physician documentation.

Here’s what coders practice:

Sequencing multi-system injury codes correctly under ICD-10 hierarchy rules.

Applying Modifiers 59 and 25 based on surgical overlaps and emergent services.

Identifying when procedures should be bundled or reported separately using current NCCI guidelines.

Making compliant decisions on whether to query physicians based on documentation shortfalls.

Each simulation ends with a feedback walkthrough, comparing coder choices with gold-standard answers reviewed by certified AAPC and AHIMA instructors. This level of feedback is critical for coders working in trauma-heavy hospitals, where split-second judgment affects both reimbursement and compliance.

Coders don't just memorize—they problem-solve in real time, strengthening their ability to apply judgment within regulatory guardrails.

Special Modules on Emergency/Ortho/GI Coding

Trauma patients don’t stick to one specialty—and neither should your training. That’s why AMBCI’s course offers focused trauma modules that span across emergency medicine, orthopedics, and gastrointestinal trauma, where the coding stakes are particularly high.

Each specialty module includes:

High-acuity ED scenarios, such as motor vehicle collisions or gunshot wounds, where coders learn to distinguish critical care billing from procedure coding.

Ortho trauma cases, focusing on fracture classifications, open vs. closed injury distinctions, and sequencing of multi-site injuries in a single claim.

GI trauma scenarios, including splenic rupture, bowel perforations, and emergency laparotomies, with special focus on differentiating exploratory vs. definitive procedures in CPT coding.

The curriculum also includes in-depth exploration of:

ICD-10 combination codes for multiple injuries and sequelae.

Proper use of external cause, place of occurrence, and activity codes for trauma reporting.

Common modifier denial traps and how to prevent them through documentation and sequencing logic.

This layered, specialty-integrated structure ensures that every coder who completes the course is fully prepared to handle high-risk trauma claims with speed, accuracy, and audit-proof compliance.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

When coding multiple traumatic injuries, coders must sequence the most severe injury first, based on clinical significance, not order of treatment. Use combination codes only when applicable (e.g., T07 for unspecified multiple injuries) and avoid coding minor wounds if deeper injuries exist at the same site. Coders should always apply distinct seventh characters (e.g., A, D, S) to reflect the phase of care. Documentation must clearly describe injury severity, laterality, and treatment to ensure ICD-10 codes fully represent the trauma complexity. Query physicians if severity or anatomical detail is missing, as this directly impacts DRG assignment and claim accuracy.

-

Common trauma CPT errors include: unbundling procedures improperly, missing or misapplying Modifier 59 or 25, and failing to distinguish surgical intent from overlapping services. Coders frequently apply modifiers to bypass edits without confirming anatomical or procedural distinctness, triggering automated denials. Another critical error is coding aborted or incomplete procedures as full surgical interventions, which can lead to overpayment and post-payment audits. Using real-time NCCI edits, CPT Assistant references, and reviewing anesthesia and nursing notes helps clarify intent. Always ensure procedural documentation aligns with coding logic, particularly when multiple body regions are involved.

-

Coders should initiate a query when documentation lacks clarity around injury location, severity, surgical intent, or care phase. For instance, if a note references “leg fracture” without specifying tibia/fibula, laterality, or open/closed status, a query is essential. In trauma, even minor gaps can lead to major reimbursement discrepancies. Queries should follow compliance standards: non-leading, timestamped, and embedded in the EHR. Proactive querying is especially important for assigning seventh characters, applying modifiers, and validating critical care services. Coders must treat queries as a routine part of trauma claim accuracy, not as an exception.

-

External cause codes (V00–Y99) are vital in trauma because they document how an injury occurred—vehicle crash, fall, assault, etc. Although these codes don’t directly affect payment, they are often mandatory for trauma registries, payer analytics, and compliance audits. In addition to the cause, coders must apply Y92 (place of occurrence) and, when relevant, Y93 (activity) codes. For example, a workplace machinery injury would include the mechanism (W31.1XXA), the site (Y92.61), and the activity (Y93.J4). Never assign an external cause code unless it's clearly documented, and always confirm that the timing aligns with the initial encounter.

-

To use Modifier 59 properly, documentation must show that two services were distinct by site, encounter, or procedural intent. For example, if both a chest tube and orthopedic fixation were performed, they must involve separate anatomical regions or incisions, and be medically necessary as individual services. Payers require coders to cite operative report phrases like “performed through a separate incision” or “performed independently.” Never rely on code combinations alone to justify Modifier 59. A compliant claim requires explicit documentation, and if clarity is missing, querying the provider is mandatory before billing.

-

Coders should only bill critical care (e.g., 99291) if time requirements are met (minimum 30 minutes) and the documentation details high-complexity decision-making and organ support. Trauma settings blur the line between resuscitation and procedural prep, so the note must distinguish critical care from procedural time. Payers deny claims if critical care overlaps with anesthesia or surgery unless both are separately supported. Key terms to include: “life-threatening condition,” “multi-organ support,” and specific time intervals. Use time-tracked EHR entries and physician attestations, and ensure the total critical care time is clearly stated and non-duplicative.

-

Bundling edits, especially from NCCI (National Correct Coding Initiative), determine whether two CPT codes can be billed together or must be combined. In trauma, overlapping procedures—like laceration repair during orthopedic surgery—may fall under comprehensive codes unless modifiers like 59 or X-series are justified. Coders must consult NCCI edits before billing and verify whether services are mutually exclusive or bundled. Payers rely heavily on these edits, and ignoring them can lead to full claim rejections or audits. Advanced trauma coders regularly cross-check these edits using AAPC or CMS tools before final claim submission.

The Takeaway

Mastering trauma coding demands more than guideline familiarity—it requires clinical insight, decision-making under ambiguity, and a firm grasp on modifier logic, documentation gaps, and payer policies. Complex trauma cases involve multi-system injuries, emergent procedures, and overlapping provider documentation, making them the most difficult and most denial-prone claims in medical coding.

By understanding ICD-10 injury hierarchies, applying CPT modifiers with surgical precision, and using physician queries proactively, coders can significantly reduce errors and improve compliance. Tools alone don’t drive accuracy—judgment and rigor do. For coders seeking to elevate their skills, certifications like the AMBCI Advanced Medical Billing and Coding Certification offer targeted training on trauma scenarios that directly impact reimbursement outcomes.

In high-stakes trauma cases, precision isn’t optional—it’s the difference between payment and penalty.