Guide to Clinical Documentation Integrity Terms

Clinical Documentation Integrity (CDI) has become a frontline function in modern healthcare. As reimbursement shifts toward value-based care and regulatory audits grow more stringent, the accuracy of clinical notes directly influences both patient outcomes and financial performance. What was once seen as an administrative task is now a high-stakes operation.

CDI is no longer just about making documentation “clear”—it’s about ensuring clinical truth aligns with coded data, supporting care decisions, and resisting payer denials. From physician queries to coder clarifications, the language of CDI is technical, high-impact, and constantly evolving. In this guide, we break down every core term you need to understand the ecosystem—terminology that doesn’t just boost compliance, but transforms clinical and operational outcomes.

What Is CDI and Why It Matters

Definition, Scope, and Impact

Clinical Documentation Integrity (CDI) refers to the systematic process of ensuring that medical records accurately represent a patient’s clinical status. It serves as the bridge between documentation, coding, quality reporting, and reimbursement. Without CDI, diagnoses may be missed, treatments misrepresented, and payments undercut.

The scope of CDI has expanded beyond inpatient records. Today, it encompasses ambulatory care, outpatient surgical centers, behavioral health, and even telemedicine. It’s no longer confined to hospital walls. CDI specialists analyze clinical narratives, identify gaps, and issue clarifications—ensuring every diagnosis, procedure, and risk factor is properly reflected.

CDI directly influences:

Quality of care metrics (readmission rates, mortality, complications)

Reimbursement and case mix index (CMI) calculations

Risk adjustment for value-based payment models

Audit defensibility in the face of payer reviews and federal oversight

Effective CDI drives organizational outcomes. Facilities with advanced CDI programs report CMI increases of 8–15%, improved coding accuracy, and decreased denial rates. In real terms, this translates into millions in revenue recovery—without any new services rendered, just more accurate representation of what’s already being done.

Who’s Involved: CDI Specialists to Coders

A robust CDI program brings together multiple stakeholders, each playing a distinct role in documentation accuracy.

CDI Specialists: Often nurses or clinical professionals trained in documentation science, they conduct concurrent reviews of patient charts. They query providers on incomplete, vague, or conflicting documentation.

Clinical Coders: Rely on documented language to assign diagnosis and procedure codes. Coders ensure documentation meets coding guidelines and payer requirements.

Physicians and Advanced Practitioners: The source of all primary documentation. Their notes must be detailed, specific, and support coding decisions. CDI queries are directed to them.

Quality and Compliance Teams: Oversee data integrity and ensure that documentation aligns with external benchmarks like HEDIS, OASIS, and CMS Star Ratings.

Revenue Cycle Management (RCM): Uses coded documentation to bill payers. CDI accuracy affects denial rates, audit risk, and net revenue.

True CDI success demands alignment between these roles. Cross-functional training, shared dashboards, and real-time feedback loops help teams close documentation gaps before claims are submitted. In the best systems, CDI isn’t a separate department—it’s a daily, collaborative process integrated into every phase of care delivery.

Core Documentation Structure Terms

Types of Clinical Notes

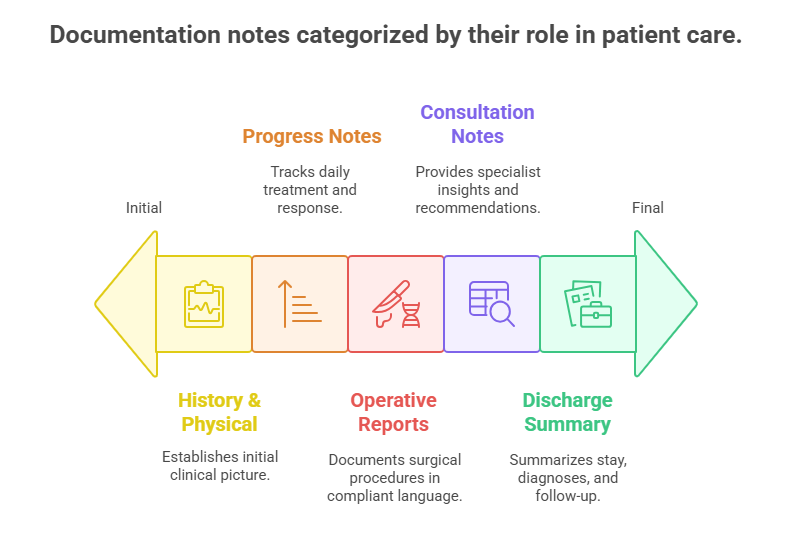

Understanding core note types is essential for any documentation integrity effort. Each note format serves a different purpose—and incomplete or inconsistent entries can trigger claim denials or audit red flags.

History & Physical (H&P): Initiated at admission or first visit, this foundational note outlines the patient’s medical history, symptoms, and physician assessment. CDI flags often originate here due to vague diagnoses or missing risk indicators.

Progress Notes: Written daily by providers, these updates chart the patient’s response to treatment, new symptoms, and changes in clinical status. CDI reviews these notes to detect evolving diagnoses not captured in the initial H&P.

Operative Reports: Document surgical procedures in exacting detail. Terminology here must align with Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and ICD-10-PCS codes. Even small mismatches—like “removal” instead of “excision”—can cause rejections.

Consultation Notes: Specialists document their findings and recommendations. CDI queries often arise when consulted specialists suggest conditions not documented by the attending.

Discharge Summaries: This comprehensive wrap-up defines the final diagnoses, procedures performed, and aftercare instructions. Payers often review these first, so errors here are especially costly.

Each of these notes must align to tell a coherent, codeable, and defensible patient story. One vague or incomplete note can unravel the entire record’s integrity.

Structured vs. Unstructured Fields

Most Electronic Health Records (EHRs) capture data using a combination of structured (clickable) fields and unstructured (free-text) entries. CDI effectiveness depends on mastering both.

Structured Fields: These are dropdowns, checkboxes, and templated fields that feed into reporting systems. They enable analytics, risk stratification, and clinical decision support. But they’re often overly rigid—missing context or specificity.

Unstructured Fields: Free-text narratives where providers elaborate on patient conditions. These carry clinical richness but are harder to analyze automatically. Coders and CDI professionals spend the most time here.

Why does this matter?

A diagnosis clicked in a structured field but not expanded in narrative may be flagged during audits.

An unstructured note may include a clinically valid diagnosis, but if it lacks standard phrasing, coders cannot assign a billable code.

Templates overused in structured notes (e.g., auto-filled normal findings) create cloning risks and undermine audit credibility.

Smart CDI systems leverage both: they extract structured data for efficiency but audit unstructured entries for clinical accuracy and billing compliance. Providers must be trained to document with both precision and context—to ensure the EHR speaks fluently to both humans and machines.

Queries, Clarifications, and Escalation Terms

Types of CDI Queries

A CDI query is a formal communication to a provider requesting clarification or additional documentation. Queries are not accusations—they are compliance tools designed to clarify vague, missing, or conflicting information. However, they must follow strict standards set by AHIMA and ACDIS to avoid leading the provider or appearing as an attempt to influence reimbursement.

CDI queries fall into four primary categories:

Concurrent Queries: Issued while the patient is still under care. These allow real-time correction and are ideal for improving final coding accuracy before discharge.

Retrospective Queries: Initiated after discharge but before claim submission. These queries resolve missed documentation issues not caught during concurrent review.

Verbal Queries: Used in fast-paced environments, especially when decisions must be made quickly. These should always be documented afterward to ensure compliance.

Written Queries: The most defensible format. Whether sent through the EHR or paper, they must include:

The specific documentation needing clarification

Clinical indicators supporting the question

A multiple-choice or open-ended question format that avoids implying a preferred answer

A compliant query is non-leading, clinically grounded, and fully auditable. Poorly written queries risk claim denials or False Claims Act scrutiny.

Response Outcomes and Documentation

Once a query is issued, provider response is critical—and each possible outcome carries implications for coding, compliance, and audit defense.

Agree: The provider confirms the clarification and updates the documentation accordingly. Coders then assign a diagnosis code based on the updated note. This is the ideal resolution.

Disagree: The provider formally disagrees with the query, and no documentation changes are made. This must be documented clearly, and the coder will code based on existing language.

No Response: If the provider fails to respond within the required timeframe (varies by facility or EHR system), the query must be closed without documentation changes. Coders cannot code based on the query content alone—the official note must reflect the diagnosis.

It’s essential that all query responses are incorporated into the legal medical record and that any changes made are:

Time-stamped

Signed by the provider

Embedded within the clinical context of the encounter

Many hospitals now track query response rates and agreement percentages as performance metrics for CDI effectiveness. Low response rates or high disagreement trends often signal either poor query design or documentation culture problems that need broader intervention.

Coding-Specific CDI Language

DRGs, MCCs, CCs

Diagnosis-Related Groups (DRGs) are the foundation of inpatient billing in the U.S. healthcare system. Each DRG is assigned based on principal diagnosis, procedures, age, discharge status, and the presence of complications or comorbidities.

DRGs: Bundled payment categories that determine how much a hospital gets reimbursed for a patient stay. A single DRG might represent thousands of dollars—making documentation alignment critical.

CCs (Complications/Comorbidities): Secondary diagnoses that moderately increase the complexity and resource use of a case. Documenting these can shift a DRG to a higher-paying version, assuming it's backed by proper clinical indicators.

MCCs (Major Complications/Comorbidities): Severe conditions that significantly raise case intensity. These often drive the highest reimbursement increase—but also carry the highest audit risk if improperly documented.

For example, documenting “acute blood loss anemia” versus just “anemia” may trigger a DRG increase from $7,000 to over $12,000, but only if the condition is supported by labs, transfusions, and narrative evidence. CDI specialists must ensure that terms align with ICD-10 coding guidelines and audit standards.

Clinical Indicators and Code Specificity

Payers and auditors demand specific, clinically supported language. Vague terms no longer make the cut.

“Urosepsis” is not billable—the provider must clarify if it’s sepsis, UTI, or both.

“CHF” needs classification—systolic vs. diastolic, acute vs. chronic, and whether it’s compensated or decompensated.

“Renal failure” must be staged—e.g., “Stage 3 chronic kidney disease,” not just “renal insufficiency.”

This is where clinical indicators come in—vital signs, imaging results, lab values, or medications that support a diagnosis. CDI professionals query providers when indicators point to a condition that is understated or undocumented.

Precision impacts:

Risk-adjusted outcomes (especially for Medicare Advantage plans)

HCC coding for chronic disease capture

Denial prevention and appeal success rates

A documentation entry that’s technically accurate but clinically vague might still be denied. CDI ensures diagnoses are specific, justified, and resilient against payer scrutiny.

| Concept | Definition / Example | Why It Matters in CDI |

|---|---|---|

| DRG (Diagnosis-Related Group) | Bundled payment category based on diagnosis, procedures, age, discharge status, and presence of CC/MCC | Drives hospital reimbursement; must align with documented diagnoses and procedures |

| CC (Complication/Comorbidity) | Moderate-severity secondary diagnosis (e.g., dehydration, anemia) | Elevates DRG weight; requires clinical support such as labs, vitals, or imaging |

| MCC (Major CC) | High-severity condition (e.g., sepsis, acute respiratory failure) | Highest impact on DRG and reimbursement; also carries highest audit risk if unsupported |

| Vague Diagnosis: "Urosepsis" | Should be documented as "Sepsis" or "UTI" | “Urosepsis” is not a billable diagnosis term under ICD-10 |

| Vague Diagnosis: "CHF" | Specify systolic vs. diastolic, acute vs. chronic, and decompensated vs. compensated | Impacts both DRG assignment and HCC capture for risk-adjusted models |

| Vague Diagnosis: "Renal Failure" | Must include staging (e.g., “Stage 3 CKD” or “Acute Kidney Injury”) | Coding guidelines require specificity; vague terms often lead to denials |

| Clinical Indicators | Labs (e.g., hemoglobin), vitals (e.g., fever), imaging (e.g., CXR), medications (e.g., diuretics) | Must support all documented diagnoses; coders and auditors rely on them to confirm medical necessity |

| Code Specificity | Use of detailed, clinically accurate terms (e.g., “acute blood loss anemia”) | Drives accurate reimbursement, reduces denials, and protects against audits |

Audit-Readiness and Compliance Language

Legibility, Timeliness, and Authorship

In the age of EHRs, legibility should no longer be a concern—yet audit reports still cite unreadable or poorly formatted entries as documentation failures. Whether handwritten or digital, documentation must be:

Clear and traceable: No ambiguous acronyms, no jargon that lacks clinical context

Time-stamped and dated: Missing timestamps or retroactive edits without clear notation can void a note’s validity

Signed with credentials: A note without provider authentication is non-billable—even if clinically complete

Timeliness is also non-negotiable. For Medicare and most payers, notes must be completed within 24 to 48 hours of the encounter. Late entries, especially those added post-discharge, are flagged during:

OIG audits

RAC reviews

Private payer investigations

In addition, authorship must be clear. Shared notes or templates that obscure who documented what can trigger fraud allegations. CDI ensures documentation flows meet standards set by CMS, AHIMA, and facility-specific medical staff bylaws.

Copy-Paste & Cloning Risks

EHR systems have made it easier—and riskier—than ever to replicate documentation. While copy-forward functions improve workflow, overuse creates serious compliance vulnerabilities.

Auditors commonly flag:

Identical progress notes across multiple days with no new assessment

Cloned physical exam findings that don't match clinical status

Persistent inclusion of resolved conditions (e.g., continuing to document “fever” post-discharge)

These are not just bad habits. Copy-paste misuse can lead to:

Upcoding accusations

Claim denials

Fines under the False Claims Act

Facilities must implement:

Cloning detection algorithms

Provider education programs

Audit trails that clearly show what content is original, edited, or copied

From a CDI standpoint, every note must reflect the actual status of the patient at the time of the visit—not a recycled version of the past. The right terminology helps distinguish between “history of,” “resolved,” and “ongoing” conditions, preventing misinterpretation and overbilling.

| Category | Compliance Requirement | CDI and Audit Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Legibility | Notes must be readable, structured, and free of ambiguous jargon | Illegible or unclear entries are often cited in audits and can invalidate records |

| Timeliness | Documentation should be completed within 24–48 hours of encounter | Late entries raise red flags during RAC, OIG, and payer audits |

| Authorship | Each note must be signed and dated with provider credentials | Unsigned or shared-template notes may trigger fraud allegations |

| Copy-Paste Overuse | Avoid identical notes across multiple dates or for different patients | Cloned content may suggest falsification, leading to claim denials or fines |

| CDI Safeguards | Terminology should distinguish between “history of,” “resolved,” and “ongoing” conditions | Ensures accurate reflection of clinical status and protects against upcoding allegations |

| Compliance Tools | Use cloning detection tools, audit trails, and targeted provider education | Helps enforce original documentation and reduce compliance risk |

How Our Medical Billing and Coding Certification Equips You for Real-World Terms

If you're serious about mastering documentation language that drives compliant billing, audit-proof claims, and accurate reimbursement, this is where it starts. AMBCI’s Medical Billing and Coding Certification goes beyond textbook definitions—every lesson is rooted in the exact terms, workflows, and real documentation breakdowns used in today’s clinical environments.

You’ll get hands-on with:

Real-world CDI queries and provider responses, so you can recognize when documentation is vague, incomplete, or audit-prone

Terminology tied directly to DRG shifts, HCC accuracy, and coding specificity, not just definitions but their financial and compliance implications

Structured vs. unstructured EHR training, so you can decode documentation no matter how it’s entered—templated, cloned, or free-text

Our curriculum includes live documentation simulations that teach you how to spot upcoding risks, resolve conflicting notes, and navigate common denial triggers. You’ll also learn to flag improper authorship, misused templates, and non-billable terminology—skills employers now expect from certified professionals.

Whether you're entering the field or upskilling for leadership roles in revenue cycle teams, AMBCI’s certification prepares you for every real-world scenario you’ll face—from payer audits to physician training. And it’s not theory. It’s built on hundreds of real case reviews, CDI workflows, and escalation scenarios you’ll use on Day 1.

Frequently Asked Questions

-

Clinical Documentation Integrity (CDI) focuses on ensuring that provider documentation fully supports diagnoses and procedures, while medical coding translates that documentation into standardized codes for billing. CDI happens before or during documentation, aiming to improve clarity, specificity, and compliance. Coding happens after documentation is finalized, where coders assign ICD-10-CM, CPT, or HCPCS codes based on what was written. CDI professionals issue queries when terms are vague or non-billable; coders rely on finalized language. Without CDI, coders may miss important diagnoses or assign incorrect DRGs, leading to revenue loss or denials. The two roles are deeply interdependent, especially in inpatient settings, where one documentation error can impact tens of thousands in reimbursement or trigger an audit. Strong CDI improves coding accuracy—and ultimately the bottom line.

-

CDI teams commonly flag nonspecific diagnoses, undocumented complications, and outdated terminology. Frequent culprits include:

“Urosepsis” (requires clarification—sepsis or UTI?)

“Failure to thrive” in adults (needs nutritional, mental, or physiological backing)

“Anemia” (should specify cause, acuity, and relation to treatment)

Abbreviations without definitions (e.g., “PNA” for pneumonia)

Other issues include overuse of templated language, copy-paste errors, and diagnoses with no clinical indicators. Phrases like “likely,” “suggestive of,” or “rule out” also get flagged unless clearly contextualized. CDI professionals look for diagnostic precision and clinical backing. If documentation lacks support from labs, vitals, or imaging, it’s queried. Every flagged term represents a risk of denial, audit, or underpayment. Precision is not optional—it’s required for compliant billing.

-

A well-placed CDI query can directly increase hospital reimbursement by capturing severity, risk, and complexity. For example, clarifying that a patient has “acute on chronic systolic heart failure” instead of just “CHF” may shift the DRG, raising payment significantly. Queries help ensure the record reflects what actually happened during care, so coders can accurately assign MCCs, CCs, or risk-adjusting diagnoses. Without these clarifications, coders must default to vague codes—lowering the Case Mix Index (CMI) and reimbursement. Queries also reduce future denials by ensuring documentation matches clinical evidence. However, queries must be non-leading, justified by indicators, and fully documented. If misused, they can backfire during audits. The right query, used the right way, transforms ambiguous care into defensible revenue.

-

Specificity determines how diagnoses and procedures are coded, reimbursed, and risk-adjusted. Vague documentation—like “renal insufficiency” instead of “Stage 3 chronic kidney disease”—limits billing potential and invites denials. Payers demand precision to validate medical necessity and support outcomes data. Specificity also affects clinical decision support, quality scores, and population health metrics. For example, “pneumonia” is not enough—it must specify type (bacterial, viral), site (left lower lobe), and source (community-acquired). Incomplete documentation leads to:

Lower DRG assignments

Missed HCC capture

Denials for unsupported procedures

CDI teams focus on getting providers to write what they mean with clinical clarity. Every word counts. Specificity ensures the medical record tells a complete story—one that survives audits, supports care, and secures payment.

-

Overuse of copy-paste or templated notes creates serious compliance risks. Auditors routinely flag cloned notes where the same language is repeated across days or patients with no clinical changes. Common issues include:

Copying outdated problems (“fever” listed days after it resolved)

Unchanged exam findings (identical vitals, unaltered assessments)

Persistent use of past diagnoses as current without clarification

This practice undermines medical necessity, leads to denials or refund demands, and increases the chance of False Claims Act violations. Even if care was appropriate, documentation must match the real-time clinical status. CDI specialists are trained to spot cloning patterns and educate providers on documenting dynamically. The EHR makes copying easy—but unless used cautiously, it can cost organizations millions in fines, audits, and credibility.

-

CDI enhances audit readiness by ensuring clinical documentation supports coded data with clarity, specificity, and compliance. Auditors—whether internal, payer-based, or federal (like RAC or OIG)—look for mismatches between notes and billing. CDI professionals prevent:

Missing diagnoses that affect DRG or HCC scoring

Inconsistent entries across providers or disciplines

Noncompliant use of terms, dates, or authorship

They also monitor for timeliness, documentation lags, and signature gaps. When CDI is active, the record is:

Internally validated

Clinically justified

Aligned with coding and billing policies

This means fewer takebacks, smoother appeals, and lower denial rates. Facilities with strong CDI programs often outperform others in payer audits—because their documentation is built to withstand scrutiny long before auditors arrive.

-

The best starting point is a certification that teaches real-world terminology, documentation standards, and compliance alignment. AMBCI’s Medical Billing and Coding Certification is ideal because it focuses not only on coding mechanics but also on how documentation must support those codes. You’ll learn:

Clinical terms that influence DRGs and HCCs

How to read and assess provider notes

CDI query formats and documentation escalation steps

Audit flags and terminologies that trigger denial risk

Hands-on case studies, EHR simulations, and coding practice exercises help solidify the material. Whether you’re a medical biller, coder, or future auditor, understanding CDI terms is a career-defining skill—and this certification gives you the real-world vocabulary to lead with confidence from day one.

Final Thoughts: CDI Terms That Safeguard Accuracy

In a healthcare system driven by precision, payment integrity, and audit resilience, clinical documentation is no longer just a record—it’s a legal, financial, and clinical asset. The right terms don’t just describe a condition—they define how it’s coded, billed, and defended. Knowing the difference between “suspected pneumonia” and “confirmed lower lobe pneumonia” can mean the difference between denial and reimbursement, or between patient misclassification and optimized care.

By mastering CDI terminology, professionals gain the power to reduce denials, protect provider credibility, and ensure compliant revenue capture. Whether you’re a coder, biller, CDI specialist, or student entering the field, your fluency in these terms is what sets you apart. Accuracy isn’t just ideal—it’s enforceable, traceable, and billable. If your documentation can’t speak the language of compliance, your claims won’t stand up to scrutiny. CDI terms aren’t optional. They’re your defense, your foundation, and your future.