ICD-11 Coding Standards & Best Practices

ICD-11 is not just “a newer ICD.” It is a different coding logic with a bigger surface area for mistakes. The fastest way teams lose accuracy is by coding ICD-11 like ICD-10, skipping postcoordination rules, and treating new concepts like extension codes as optional. Payers, auditors, and quality teams will not grade you on effort. They will grade you on reproducible logic and documentation support. This guide gives you the coding standards, workflow controls, and audit safe habits that keep ICD-11 claims defensible and your productivity stable.

1) ICD-11 Standards That Matter in Real Workflows

Most ICD-11 errors happen for predictable reasons: weak understanding of the code architecture, inconsistent use of postcoordination, and poor alignment between documentation and what the code actually asserts. If your ICD-11 output changes coder to coder for the same chart, you do not have a knowledge problem. You have a standardization problem.

Start by treating ICD-11 like a rules driven language. Every diagnosis statement in ICD-11 should answer four questions consistently:

What is the core condition and what is its accepted ICD-11 term

What is the clinical context that changes meaning, severity, or subtype

What extensions are required to represent laterality, timing, or encounter level concepts where applicable

What evidence exists in the record to support each added attribute

This is the same mindset used in high scrutiny work such as medical coding audit terms where every coded statement must survive a second reviewer. When you build ICD-11 as a controlled process, you reduce disputes, fix “coder drift,” and make training scalable.

A practical way to raise consistency is to maintain a small internal “ICD-11 dictionary” for your common service lines, modeled after AMBCI’s specialty references like ICD-11 mental health coding definitions, ICD-11 neurology codes reference, and ICD-11 respiratory coding essentials. Use them as style guides for how to define terms, document proof points, and keep code selection aligned to clinical language.

ICD-11 also forces a higher bar for internal QA because postcoordination makes it easy to over specify. Over specification is a silent denial driver. It can make the code look “more severe” than the documentation proves, which triggers medical necessity edits and retrospective audits. Build guardrails with a compliance lens using coding compliance trends and keep an eye on the bigger regulatory direction discussed in upcoming regulatory changes affecting medical billing.

Finally, do not treat ICD-11 adoption like a “go live moment.” Treat it like an ongoing quality program. You need measurable standards: accuracy rate by specialty, postcoordination completeness rate, query rate, and overturn rate in QA. Pair that measurement mindset with process modernization ideas from AI in revenue cycle management and skill building guidance from future skills medical coders need.

2) ICD-11 Code Architecture and Postcoordination Without Errors

If you want ICD-11 accuracy, you must understand how ICD-11 represents meaning. ICD-11 expands the ability to create a precise clinical statement by combining a stem concept with additional qualifiers. That is powerful, but it is also where denials and QA failures are born.

A practical standard is to treat every ICD-11 cluster as a sentence. Before you finalize, read it as if you are presenting it to a clinician and an auditor. If the cluster asserts something the provider did not clearly document, it is not a “close enough” issue. It is a compliance exposure. This is why teams that already operate with audit rigor do better. Use the frameworks in medical coding audit terms and apply them to ICD-11 clusters as a routine step.

Postcoordination discipline has three rules that protect you:

Add qualifiers only when they change the clinical meaning in a way the record supports

Avoid stacking qualifiers when one is sufficient to represent the documented concept

Prefer clarity over maximal specificity when documentation is not explicit

A common trap is “coding to the plan.” Providers often document suspected diagnoses, rule out language, or anticipated severity. Coders who convert that into a definitive coded statement create downstream denials and audits. Set a strict standard for uncertainty and confirmation. When you handle this correctly, it aligns with payer logic similar to what you see when interpreting denial language in the EOB guide.

Another high risk area is chapter specific nuance. ICD-11 has different patterns across clinical domains. Train coders first on your highest volume and highest denial risk categories. For many organizations, that means respiratory, infectious disease, neuro, and behavioral health. Use AMBCI’s references like respiratory diseases explained, infectious diseases and pandemics guide, neurological disorders reference, and mental health coding dictionary as your training model.

Finally, treat crosswalking as a risk control, not a coding method. ICD-10 to ICD-11 mappings can point you in the right direction, but they can also create false equivalence. The standard should be: map, then validate meaning. This approach mirrors the discipline required in high-stakes coding contexts discussed in coding compliance trends and the policy awareness in how new healthcare regulations impact coding careers.

3) Documentation Alignment, Provider Queries, and “Audit Safe” Specificity

ICD-11 is unforgiving when your documentation is thin. The solution is not to “code less” across the board. The solution is to code precisely where documentation supports it and to have a reliable query threshold where it does not.

Set a clear internal rule: if an added qualifier changes severity, type, or causation, it needs explicit support. That support can be a direct provider statement, measurable clinical indicators, or linked assessment. When that support is missing, you choose one of two compliant paths: query or select a less specific code. This is not just a quality choice. It is a denial prevention strategy.

Provider queries should be treated like production tools, not awkward interruptions. The fastest way to make queries useful is to standardize them:

State the clinical fact pattern in neutral language

Provide two or three clinically reasonable options

Ask the provider to clarify what is truly present

This reduces back and forth and increases response rates. It also improves your defensibility, because your coding decision becomes traceable. Build query logic using the same decision clarity you apply when resolving payer responses in the EOB guide and the same documentation integrity mindset highlighted in medical coding audit terms.

A strong ICD-11 documentation standard also requires you to limit “problem list cloning.” Many charts contain outdated diagnoses that are carried forward with no active management. Coding those without relevance creates noise and can distort risk and reporting. Your standard should require relevance evidence, active management, or direct relation to the encounter. This aligns with the compliance posture discussed in coding compliance trends and helps you avoid hidden audit exposure.

Use specialty based evidence anchors to reduce subjectivity. For example:

Respiratory conditions should tie to objective respiratory findings or documented clinical assessment, supported by patterns in respiratory coding essentials

Neurological conditions should tie to documented exam findings, imaging, or assessment logic modeled in neurological disorders reference

Infectious disease coding should reflect confirmed organism or diagnostic basis consistent with infectious diseases and pandemics guide

Behavioral health coding should align to documented diagnostic criteria and functional impact like mental health coding definitions

This is how you keep specificity audit safe without slowing down throughput.

4) QA Controls That Prevent ICD-11 Denials and Audit Findings

ICD-11 success is not about one coder being excellent. It is about making the system consistent so the average coder produces audit safe output. That requires QA controls designed for ICD-11 realities.

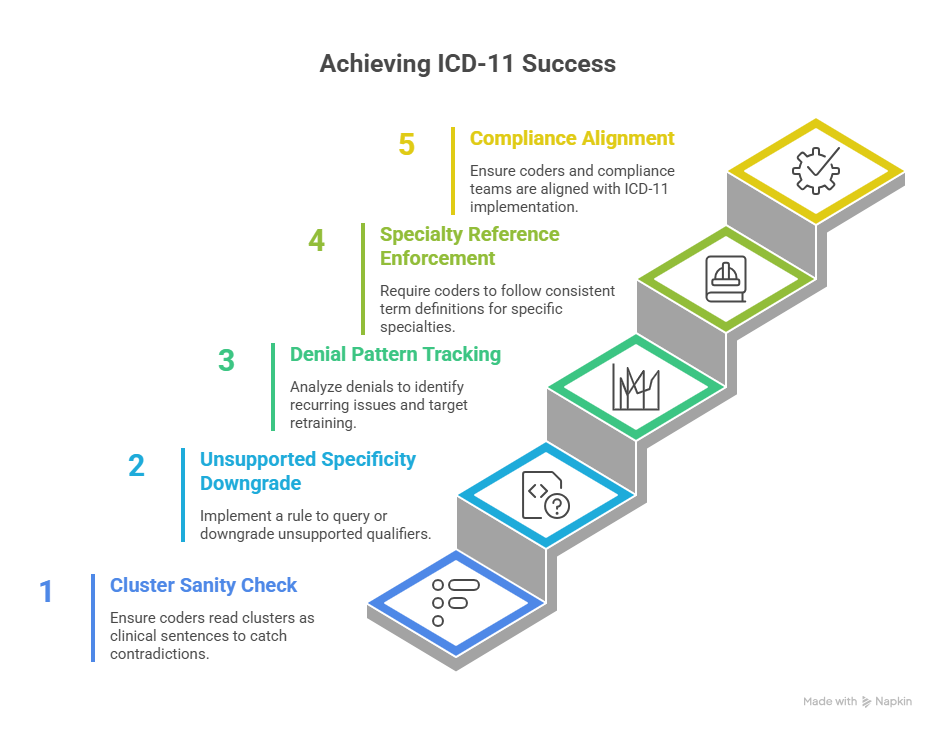

Control 1 is the cluster sanity check. Require coders to read the final cluster as a clinical sentence and verify it matches documentation. This catches contradictions like severity without evidence, laterality without explicit notes, or causation implied without linkage. The best QA reviewers do this instinctively. Your standard should make it mandatory, and you can teach it using patterns from medical coding audit terms.

Control 2 is the “unsupported specificity downgrade” rule. When QA sees a qualifier that lacks support, the remedy is not argument. The remedy is either query or a more general code. This is the same logic used when managing payer pushback and reading decision language in the EOB guide.

Control 3 is denial pattern tracking. ICD-11 makes it easy to create unique clusters, which means denials can look random. They are not. They cluster around the same few issues: over specified acuity, complication assumed without linkage, and comorbidities coded without encounter relevance. Track denials like an analytics problem using concepts from predictive analytics in billing, and then target retraining where the data proves it.

Control 4 is specialty reference enforcement. If you code high volume respiratory, neuro, infections, or behavioral health, your QA should require coders to follow consistent term definitions and evidence anchors. Use AMBCI style references like respiratory coding essentials, neurology code reference, infectious disease ICD-11 guide, and mental health dictionary as your baseline training library.

Control 5 is compliance alignment. ICD-11 is usually implemented alongside other workflow changes. That increases risk if your compliance team is not aligned to how coders are using new specificity options. Keep the program aligned using coding compliance trends and broader perspective from how regulations impact coding careers.

5) Productivity, Tools, and “Safe” Automation for ICD-11 Coding

ICD-11 can either slow you down or make you faster. The difference is whether your tooling supports consistent decision making or forces you to rebuild logic every chart.

Start with templates that support standards. A strong ICD-11 template is not a list of codes. It is a decision scaffold:

Preferred clinical terms for your top diagnoses

Required evidence anchors for each high risk qualifier

Common query prompts for missing critical details

“Do not code” reminders for inferred information

This reduces cognitive load and cuts error rates. It also reduces reviewer disagreements because the coding choices become standardized. Build this the same way organizations build structured workflows for evolving reimbursement landscapes in Medicare reimbursement reference and policy changes in future Medicare and Medicaid billing regulations.

Automation can help, but only when you treat it as suggestion, not authority. ICD-11 automation often fails in predictable ways: it over selects specificity, it misreads copied template text, and it confuses historical diagnoses with active problems. If your team uses AI or automation, you need guardrails that mirror AMBCI’s forward-looking guidance such as AI in revenue cycle management and the capability expectations in future coder skills.

A safe approach looks like this:

Automation proposes a code cluster

Coder validates each qualifier against explicit documentation

QA audits automation heavy charts at a higher rate until stability is proven

Denials are traced back to cluster patterns and retraining is targeted

This is how you get speed without risking compliance. It also builds a defensible story if auditors ask how decisions were made, which aligns with the process orientation taught in coding compliance trends.

If you want a practical rollout strategy, do it in phases:

Phase 1: Train the highest volume diagnoses first using specialty references like respiratory coding essentials and mental health definitions

Phase 2: Implement query thresholds and cluster review controls using audit terms training

Phase 3: Add denial analytics feedback loops using predictive analytics guidance

Phase 4: Align to broader policy direction with regulatory change updates

That sequence is how you keep productivity stable while raising accuracy.

6) FAQs

-

Standardize the top 20 diagnoses per specialty and enforce a short checklist for qualifiers. Most errors come from a small set of repeated problems, especially unsupported specificity. Use a reference driven approach modeled after ICD-11 respiratory coding essentials and ICD-11 mental health definitions. Then add a cluster review step and a query threshold rule, both reinforced by coding audit terminology.

-

Treat specificity as evidence based. If the record does not explicitly support severity, type, trigger, laterality, or causation, do not add it. Choose a less specific option or query. Over-coding is not “better coding.” It is an audit risk. Build compliance guardrails using coding compliance trends and use denial language logic from the EOB guide to align coding decisions to what payers challenge.

-

Use mapping as a pointer, then validate meaning and documentation support. Mapping tools can create false equivalence where the ICD-11 concept is more specific or structured differently. Your standard should be “map, validate, finalize.” Then track outcomes through QA and denials like an analytics program using predictive analytics in billing so the mapping process improves over time.

-

If the provider documents uncertainty, you should follow your internal standard for uncertain diagnoses and code symptoms or findings where appropriate. The highest risk mistake is coding a suspected diagnosis as confirmed. Build a query threshold rule and train coders to escalate ambiguous cases. This aligns with the audit defense mindset in medical coding audit terms and helps prevent denial cycles you later have to interpret using EOB language.

-

Three checks deliver the fastest wins. First, a cluster sanity check where the reviewer reads the code cluster as a sentence and verifies it matches documentation. Second, an unsupported specificity downgrade rule where qualifiers without proof are removed or queried. Third, denial pattern tracking to identify which specialties and qualifiers create payer pushback. Build these controls using the process discipline in coding compliance trends and the measurement approach in predictive analytics.

-

Use AI as a draft assistant, never as the final decision maker. Require coders to validate each qualifier against explicit documentation. Increase QA sampling for automation assisted charts until error rates stabilize. Track denials linked to AI suggested clusters and retrain based on what payers reject. This is the safe version of modernization discussed in AI in revenue cycle management and the capability expectations in future coder skills.

-

Train where you have the highest volume and the highest audit sensitivity. For many organizations that means infectious diseases, respiratory, neurological disorders, and mental health. Build your training library using AMBCI style references such as infectious diseases ICD-11 guide, respiratory essentials, neurology codes reference, and mental health coding definitions. Then align policy awareness using upcoming regulatory changes so your standards stay current.