Infusion & Injection Therapy Billing Terms Explained

Infusion and injection billing is where small documentation misses turn into big revenue leaks. One missing stop time, one wrong “initial” selection, or one unreported drug waste can flip a high value encounter into edits, denials, and weeks of appeals. In 2026, payers are stricter on time based hierarchy, modifier integrity, and drug unit accuracy across outpatient clinics, hospital infusion centers, and physician offices. This dictionary breaks down the terms that actually control payment, so coders can bill clean, defend claims fast, and stop repeating the same avoidable mistakes.

1: Infusion Billing Language That Drives Reimbursement and Denials

Infusion and injection services are built around a hierarchy that many teams still treat like “common sense.” That mindset gets punished. Payers adjudicate based on documented start stop time, correct “initial versus subsequent” selection, and correct separation of sequential versus concurrent services. If your team understands reimbursement logic from Medicare reimbursement and denial interpretation via an EOB guide, you already know the pattern: payers do not deny because care was delivered, they deny because the record fails to prove the billable structure.

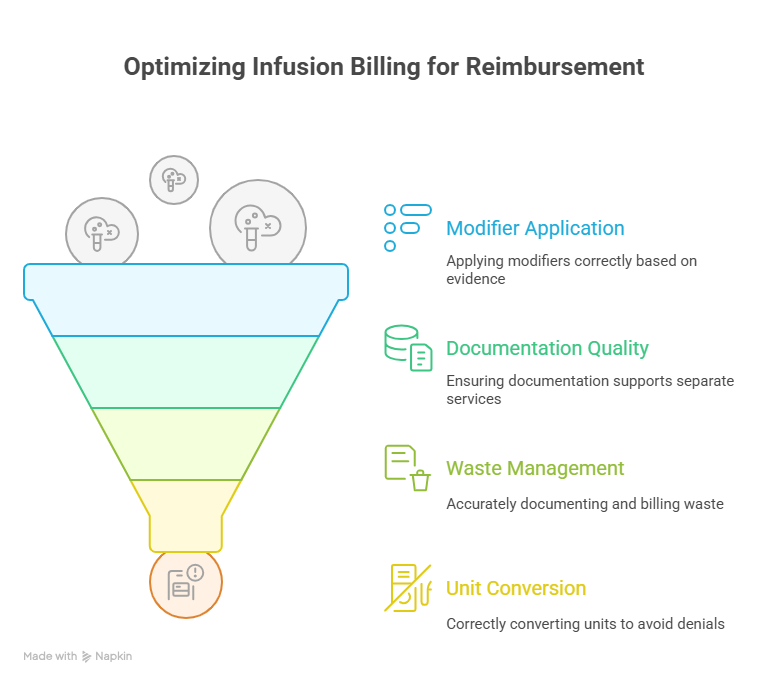

Infusion billing is also a modifier battlefield. Missing or misusing modifiers can trigger NCCI edits, push claims to manual review, and expose compliance risk. That is why strong teams train using modifier application and stay current with coding compliance trends. Infusion coding is not a “memorize a few CPT codes” job. It is a precision process tied to payer policy, documentation standards, and denials intelligence.

Infusion work also intersects multiple specialties. You see radiology injectables, ED pushes, GI biologics, oncology regimens, and cardiac drips, all billed under different operational pressures. That is why coders who cross train with radiology CPT coding, emergency medicine CPT codes, and gastroenterology CPT coding usually outperform specialists who only know one lane.

| Term | Clear Definition | Billing Impact, What Breaks If Missed |

|---|---|---|

| Initial Service | The primary infusion or injection service that anchors hierarchy for the encounter. | Wrong “initial” selection causes incorrect line ordering and frequent denials or downpayment. |

| Subsequent Service | Additional infusion or injection performed after the initial service. | Billing as initial can trigger edits and improper payment findings. |

| Sequential Infusion | A different drug or service infused one after another through the same IV access. | Mislabeling as concurrent can collapse billable units and invite payer review. |

| Concurrent Infusion | Two infusions running at the same time, typically through the same access site. | Often misbilled, payers challenge when documentation does not prove overlap timing. |

| IV Push | Medication administered by IV push, not time based infusion. | Confusing push with infusion creates mismatched time logic and denials. |

| Infusion Start Time | Documented time infusion begins. | Missing start time breaks time based billing and drives downcoding. |

| Infusion Stop Time | Documented time infusion ends. | Missing stop time is a top cause of infusion denials and audit findings. |

| Time Based Units | Units derived from total documented infusion time and code rules. | Incorrect units cause overpayment risk or underbilling revenue leakage. |

| Hydration Infusion | IV fluids billed when medically necessary and documented as such. | Frequently denied when documented as routine, convenience, or “keep vein open.” |

| Therapeutic Infusion | Infusion for treatment, not hydration, and not chemotherapy. | Must align to drug order and diagnosis support or it triggers medical necessity denials. |

| Chemotherapy Administration | Chemo and other highly complex biologic administration services. | Hierarchy differs from therapeutic codes, miscoding is a high audit target. |

| Drug HCPCS J Code | HCPCS code representing the billed drug and unit definition. | Wrong J code or units leads to immediate payer edits and recoupments. |

| NDC (National Drug Code) | Drug identifier often required in addition to J code, with unit quantity. | Missing or mismatched NDC is a common rejection and denial driver. |

| NDC Unit of Measure | NDC reporting basis such as mL, unit, gram, or international unit. | Wrong UOM makes billed quantity fail payer validation logic. |

| Drug Waste | Unused portion of a single dose vial that is discarded. | If waste is not documented and billed properly, you lose revenue or fail compliance. |

| JW Modifier | Modifier used to report drug amount discarded when allowed. | Missing JW when waste exists can cause underbilling or payer disputes in audits. |

| JZ Modifier | Modifier indicating no discarded drug from single dose container. | Required by some payers, missing it can trigger rejections. |

| NCCI Edit | Bundling rule that prevents payment for code pairs not allowed together. | If you do not understand bundling, you bill services that will never pay. |

| MUE (Medically Unlikely Edit) | Maximum units typically allowed for a code on a single day. | Exceeding MUE triggers denials or manual review, often avoidable with correct units. |

| Modifier 25 | Significant separately identifiable E and M service on the same day. | Weak documentation leads to E and M denial even if infusion pays. |

| Modifier 59 | Indicates a distinct procedural service when bundling would otherwise apply. | Overuse is an audit target, underuse causes avoidable bundling denials. |

| X Modifiers (XE, XS, XP, XU) | More specific alternatives to modifier 59 depending on payer policy. | Using the wrong distinctness modifier leads to edits and payment delays. |

| Revenue Code 026x | Hospital outpatient revenue codes commonly tied to infusion services. | Mismatch between revenue code and CPT can trigger claim edits. |

| Buy and Bill | Provider purchases drug, administers, and bills payer for drug plus administration. | Inventory and documentation accuracy are essential, mistakes create recoupment risk. |

| Prior Authorization | Payer approval required before drug or service is covered. | Missing auth can lead to full denial even with perfect coding. |

| Medical Necessity | Proof the service is reasonable and required for diagnosis and clinical status. | The number one umbrella reason behind infusion denials and ADRs. |

| LCD / NCD | Local or National Coverage Determination rules for coverage. | If diagnosis or documentation does not meet coverage rules, denials are predictable. |

| ABN (Advance Beneficiary Notice) | Notice to Medicare patient when service may not be covered. | Missing ABN can block patient billing when payer denies. |

| 835 Remittance | Electronic remittance advice showing payment and denial details. | Used to map denial patterns and prioritize fixes. |

| CARC / RARC | Codes explaining adjustment and remark reasons on remittance. | Critical for appeals, without them teams chase the wrong problem. |

| Charge Capture | Process of recording billable services, time, supplies, and drugs. | If capture is late or incomplete, revenue is lost permanently. |

| CDM (Charge Description Master) | Hospital billing catalog mapping services and supplies to codes and charges. | Bad CDM mapping creates systematic denials at scale. |

2: Service Hierarchy Terms, Initial vs Subsequent, Sequential vs Concurrent, and Time Rules

Infusion billing becomes easy only when you stop thinking “what was given” and start thinking “how was it delivered and documented.” The hierarchy starts with identifying the true initial service. That is the service that anchors the rest of the lines and tells the payer which work is primary. If your team struggles with hierarchy, you should treat it like reimbursement training and review Medicare reimbursement, then connect payment outcomes back to denial language seen in an EOB guide. The financial impact is not theoretical, it shows up as downpayments and bundling.

Time logic is the second gate. Infusions are time based, and time based means documentation is king. Start time and stop time need to be explicit, consistent, and tied to each infusion. If documentation only shows “infusion completed,” the payer can treat your units as unproven. This is where coders who understand compliance expectations win, because they know what reviewers look for in coding compliance trends and how policy shifts increase scrutiny like upcoming regulatory changes. In 2026, clean time stamps are not optional, they are reimbursement defense.

“Sequential” and “concurrent” are constantly misused. Sequential is one infusion after another, different drug, same access. Concurrent is overlap. Payers challenge concurrent billing because overlap is easy to claim and hard to prove. If you bill concurrent without documentation showing overlap, you are building your own denial. When teams want a shortcut, they often misuse modifier logic, which is why training with modifier application matters. The goal is not to “force payment,” the goal is to bill only what is defensible.

Injection terms also sit inside this hierarchy. An IV push is not a short infusion. It has its own definition and its own add on logic for additional pushes. If staff document an IV push like an infusion, your claim becomes internally inconsistent. That inconsistency is exactly what payers use in audits, which is why audit vocabulary from medical coding audit terms pairs well with infusion billing training. Clean documentation is not only about getting paid, it is about not getting recouped later.

3: Drug Billing Terms, J Codes, NDC Reporting, Units, and Waste Logic

Most infusion revenue lives in the drug, not the administration. That means drug billing accuracy is where you either protect margin or bleed it. “J code” is not just a code, it is a unit definition. If the J code unit is per 10 mg but your system bills per 1 mg, you will fail payer validation or trigger recoupment. If your team is not fluent in remittance and denial language, the fix cycle becomes slow and expensive, so train your denial readers with an EOB guide and teach cost impact with Medicare reimbursement. That is how you turn “coding errors” into measurable process improvements.

NDC reporting is another common failure point. Many payers require NDC plus quantity plus unit of measure that matches the package. The NDC line is a validation gate. If you report the wrong unit of measure, even if the drug was correct, the payer can reject the claim. This is why “charge capture” and “CDM mapping” matter as much as coder skill. A clean workflow ensures the order, dispense record, administration record, and claim line all match. When they do not match, your denial volume climbs, and you start living inside rework.

Drug waste is where compliance and revenue collide. If you discard drug from a single dose vial, you often need separate reporting logic. Underreporting waste can lose legitimate reimbursement. Overreporting waste without documentation can become a compliance issue. The safest approach is consistent documentation of dose ordered, dose given, amount discarded, and reason. Then billing can apply waste modifiers where required. If you want to build a compliance ready workflow, anchor it in coding compliance trends and broader policy awareness like future Medicare and Medicaid billing regulations. In 2026, payers are not getting softer on drug integrity, they are getting sharper.

Prior authorization terms also matter here. Many infusion drugs are high cost and require payer approval before administration. If authorization is missing or mismatched to the drug, your claim can be denied in full even with perfect coding. That is why infusion centers that win long term build a pre service verification system that checks authorization, coverage criteria, and documentation completeness before the first drop hits the line.

Infusion also crosses specialties. Injectables appear in imaging, ED, GI, and cardiology. If you want stronger cross training, build reference habits with radiology CPT coding, emergency medicine CPT codes, and cardiology CPT coding. The same drug billing terms show up everywhere, only the operational context changes.

4: Modifier, Edit, and Bundling Terms That Decide What Actually Pays

Infusion claims fail less from “wrong code” and more from “right code, wrong relationship.” That relationship is controlled by edits and modifiers. NCCI edits represent payer logic that certain services are bundled unless you can prove they were truly distinct. If your team uses distinct service modifiers as a brute force tool, you invite audits. If your team refuses to use them when appropriate, you lose legitimate reimbursement. The professional approach is evidence first, modifier second, supported by training like modifier application and audit reasoning from medical coding audit terms.

Modifier 25 is a recurring denial source in infusion settings. Many infusion visits include an E and M, but payers will deny E and M if documentation does not show a separately identifiable evaluation that goes beyond the work of ordering and supervising the infusion. If you want to reduce this denial bucket, build a checklist based on payer reasoning you see on the EOB guide and connect it back to reimbursement impact taught in Medicare reimbursement. The point is to document and bill the evaluation only when it is truly separate and provable.

Waste modifiers also require discipline. If your records do not clearly show ordered dose, administered dose, and discarded dose, adding waste modifiers is risky. But if waste exists and you fail to bill it when allowed, you leave money on the table. This is where compliance and revenue meet, so align your waste workflow with coding compliance trends and policy direction like future Medicare and Medicaid billing regulations. In 2026, payers expect consistency, not improvisation.

Also watch MUE logic. Exceeding unit caps can auto deny even when services were real. Most MUE failures trace back to incorrect unit conversion, duplicated charge capture, or misunderstanding add on rules. If you fix those upstream, your denial volume drops without adding staff. This is also why infusion teams increasingly use analytics to spot repeat patterns, a trend that ties into predictive analytics in medical billing and modern automation workflows in AI in revenue cycle management.

5: Coverage, Denial, and Compliance Terms Infusion Teams Must Track in 2026

Infusion claims do not exist in a vacuum. Coverage rules are a gate, and if you miss the gate, coding cannot save the claim. LCD and NCD language matters because it defines which diagnoses support coverage for certain drugs or services. That means coders need to understand documentation support and diagnosis pairing, then validate denial reasons quickly using an EOB guide. When denials come back, the team should already know whether it was a documentation failure, an authorization failure, a coverage mismatch, or an edit and modifier issue.

Prior authorization is one of the most brutal denial types because it often results in a full denial, not a partial adjustment. Infusion centers that survive long term treat authorization verification as part of the clinical workflow, not a billing afterthought. If authorization is denied, you need ABN logic where applicable, patient communication protocols, and clean documentation on informed consent and financial responsibility. That workflow protects revenue and reduces patient disputes.

Compliance pressure is also increasing. When payers see aggressive billing patterns, they respond with audits, documentation requests, and recoupments. Staying ahead means building education around coding compliance trends, tracking policy updates like upcoming regulatory changes, and understanding the larger policy environment through future Medicare and Medicaid billing regulations. Infusion is high cost care, so it gets reviewed like high risk revenue.

Technology is reshaping denial prevention. Teams increasingly use automation to validate NDC quantity, unit conversion, modifier logic, and documentation completeness before claims drop. That is where how automation will transform billing roles and the future skills medical coders need become practical, not theoretical. Tools can reduce error volume, but only if your team knows what the tool is checking and why.

Finally, infusion touches multiple specialty claim types. If your denial patterns show up around ED meds, imaging contrast, or GI biologics, strengthen your baseline references with emergency medicine CPT codes, radiology CPT coding, and gastroenterology CPT coding. Denial prevention improves when coders understand the clinical flow behind the charges.

6: FAQs, Infusion and Injection Therapy Billing Terms

-

Missing or inconsistent start and stop times is the biggest repeat offender, because time based billing requires provable duration, not assumptions. If the record only shows “infusion completed,” the payer can downcode or deny because units are not supported. The fix is a standardized documentation template that records each service start and stop time, plus drug name, dose, route, and reason for therapy. Then tie denial learning back to payer language using an EOB guide and financial impact using Medicare reimbursement.

-

The initial service is the primary infusion or injection that anchors the hierarchy for that encounter. It is not “the first thing administered” in every scenario. It is the first billable service in the hierarchy order based on code family and payer rules. If your team keeps flipping initial and subsequent lines, you will see edits and downpayments. Build a hierarchy cheat sheet, then validate outcomes by reading denials with an EOB guide and reviewing payer expectations through coding compliance trends.

-

Sequential means infusions happen one after another, different drug or service, same access, no overlap. Concurrent means overlap, which requires documentation proving that overlap occurred. Because concurrent billing can be abused, it is heavily challenged. If documentation cannot prove overlap timing, bill sequential or do not bill concurrent. When in doubt, prioritize defensibility and follow distinct service guidance from modifier application and audit logic from medical coding audit terms.

-

Because NDC reporting is a validation gate and it must match the dispensed product package, unit of measure, and quantity. A correct J code with an incorrect NDC quantity can still fail payer edits. The solution is a workflow that ties pharmacy dispense records to billing, with unit conversion checks and denial trend monitoring. Teams that use analytics and automation reduce this rejection bucket faster, which connects to predictive analytics and tools discussed in AI in revenue cycle management.

-

Only when the provider performed a separately identifiable E and M service that goes beyond routine pre infusion assessment and supervision. If the note does not show separate medical decision making, payers often deny the E and M line even when the infusion pays. The safest workflow is documentation first, then modifier, aligned to payer logic you see in an EOB guide and best practices from modifier application.

-

Document ordered dose, dose prepared, dose administered, amount discarded, and the reason discard occurred. Tie it to vial size and patient specific dosing, and keep it consistent between nursing documentation and pharmacy records. This protects both revenue and compliance, especially under tightening scrutiny reflected in coding compliance trends and policy direction in future Medicare and Medicaid billing regulations.

-

Denials intelligence, unit conversion accuracy, modifier discipline, coverage rule awareness, and the ability to work with automation tools without trusting them blindly. The best coders can translate payer feedback into process fixes, not just resubmissions. Build those skills by learning future skills medical coders need, understanding where tools fit via AI in revenue cycle management, and staying ahead of policy shifts through upcoming regulatory changes.