Clinical Documentation Improvement (CDI) Terms Dictionary

CDI is where coding stops being “pick the right code” and becomes “prove the right story.” In real revenue cycle work, payers do not deny because your ICD code exists. They deny because documentation fails to support medical necessity, fails to show clinical specificity, or fails to connect diagnosis to treatment. If you want clean claims, fewer queries, and fewer clawbacks, you need a working vocabulary that matches audit language, denial logic, and reimbursement rules. This CDI dictionary translates the terms that actually move money, reduce risk, and make your documentation defensible under review.

1: CDI Terms That Control Payment, Denials, and Audit Risk

CDI is not a “nice to have.” It is the difference between a claim that sails through and a claim that gets stuck in denial hell. Most denials begin with documentation gaps that coders are forced to guess around, then reviewers punish the guess. If you want to code with confidence, learn CDI terms the same way you learn payer logic in an EOB guide and the same way you learn reimbursement rules in Medicare reimbursement. CDI language is how you defend “why this code” under scrutiny.

The fastest way to think like a CDI pro is to adopt an auditor mindset. You are not writing documentation for your team, you are writing it for a stranger who only trusts what is explicitly documented. That is why you should pair CDI learning with audit vocabulary from medical coding audit terms and compliance context from coding compliance trends. The goal is simple, make the record impossible to misinterpret.

CDI also intersects with modern technology. Tools can surface gaps, but they can also scale weak templates. If you are not careful, automation creates “clean looking” notes that collapse under review. That is why CDI teams should understand where AI in revenue cycle management helps and where the future of medical coding with AI creates new compliance exposure. CDI exists to protect accuracy, not to decorate documentation.

The dictionary table below is built for daily use. It focuses on CDI terms that impact physician queries, diagnosis specificity, risk adjustment, denial prevention, and audit defense. Use it alongside workflow playbooks and payer rules like future Medicare and Medicaid billing regulations and upcoming regulatory changes.

| CDI Term | Clear Meaning | Why It Matters in Coding, Billing, and Denials |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical Indicators | Objective findings that support a diagnosis, severity, or complication. | Indicators justify specificity, reduce “unsupported diagnosis” denials, and strengthen appeals. |

| Documentation Gap | Missing clarity between what happened clinically and what is written. | Gaps create coder guesswork, then audits punish the assumption. |

| Query | A compliant request to clarify documentation. | Done right, prevents denials, improves coding accuracy, reduces post bill rework. |

| Compliant Query | Neutral wording that avoids leading the provider. | Protects against allegations of upcoding, supports compliance and audit defense. |

| Leading Query | A query that pushes a specific diagnosis or severity. | High risk behavior, can trigger compliance findings and payer disputes. |

| Open Ended Query | Provider responds in free text rather than choosing from options. | Useful when multiple diagnoses are possible, reduces bias and supports integrity. |

| Multiple Choice Query | Neutral options plus “other” and “unable to determine.” | Faster provider response, but must remain compliant and non leading. |

| Clinical Validation | Confirming a documented diagnosis is supported by clinical facts. | Prevents “diagnosis not supported” denials and recoupments. |

| DRG Validation | Ensuring diagnoses and severity justify the assigned DRG. | Critical for inpatient payment integrity and appeal readiness. |

| CC (Complication or Comorbidity) | Condition that increases complexity and can affect DRG. | If not documented clearly, expected reimbursement becomes a denial risk. |

| MCC (Major CC) | Higher severity condition with larger reimbursement impact. | Requires strong support, weak MCC documentation is a prime audit target. |

| POA (Present on Admission) | Whether a condition existed at admission or occurred after. | Wrong POA can cause quality penalties, payment disputes, and audit findings. |

| Principal Diagnosis | Primary reason for the encounter after study. | Wrong principal choice breaks claim logic and drives denials. |

| Secondary Diagnosis | Additional conditions affecting care or resource use. | Only valid when it impacts treatment, monitoring, or care plan. |

| Specificity | Level of detail, site, laterality, acuity, cause, severity. | Low specificity increases denial risk and can reduce reimbursement. |

| Acuity | Severity and time course, acute, chronic, acute on chronic. | Missing acuity leads to miscoding and “not supported” challenges. |

| Etiology | Cause of the condition, infectious, traumatic, medication induced. | Correct etiology supports correct code selection and reduces audit exposure. |

| Laterality | Right, left, bilateral, unspecified. | Unspecified laterality causes rework, rejections, and payer pushback. |

| Stage | Disease staging, pressure injury stages, CKD stage. | Missing stage breaks specificity and can invalidate risk and payment logic. |

| MEAT | Monitor, Evaluate, Assess, Treat, evidence the condition is addressed. | Prevents “problem list only” coding, supports accurate secondary diagnoses. |

| Problem List Inflation | Listing conditions without evidence they impact care. | Triggers audits and denials, especially in risk adjustment contexts. |

| Clinical Ambiguity | Documentation supports more than one interpretation. | Ambiguity creates coder inconsistency, inconsistency creates audit risk. |

| Underdocumentation | Clinically true facts not recorded in the chart. | Causes downcoding, missed risk capture, and avoidable denials. |

| Overdocumentation | Excess detail without relevance, often templated. | Creates contradictions, reviewers use contradictions to deny or recoup. |

| Contradictory Documentation | Parts of the record conflict, for example H and P vs progress note. | One contradiction can invalidate the whole severity story under review. |

| Query Opportunity | A gap that should be clarified to code accurately. | Tracking opportunities improves provider education and reduces denial rates. |

| Provider Agreement Rate | Percent of queries where provider clarifies as requested. | Low rate signals poor query quality or poor provider training. |

| Query Turnaround Time | How fast providers respond to CDI queries. | Slow responses delay coding, delay billing, delay cash. |

| DRG Impact | How documentation changes reimbursement group assignment. | Used to prioritize high risk charts and reduce revenue leakage. |

| Denial Prevention | CDI actions that reduce payer denials before they occur. | One strong clarification can eliminate months of appeals and rework. |

2: CDI Query and Clarification Terms That Separate Pros From Rework Machines

If you want fewer denials, build a query process that is fast, compliant, and defensible. A bad query does two things. It wastes provider time, then it creates a compliance liability because it looks like you pushed a diagnosis. That is why “compliant query” is not a buzzword. It is your protection layer, the same way coding compliance trends protect organizations from preventable risk.

The most common query failure is asking for a diagnosis without tying it to clinical indicators. Instead, frame the question around documented facts, then ask for clarification. You are not trying to win a code. You are trying to remove ambiguity. When ambiguity remains, your team gets inconsistent coding, and inconsistency is what payers exploit in reviews and audits. If your team handles denials, use payer language training from an EOB guide and reimbursement grounding like Medicare reimbursement to make queries reflect what payers actually require.

A professional query workflow also respects timing. Concurrent queries reduce rework because they resolve gaps while the clinical picture is fresh. Retrospective queries often feel like a trap to providers and create friction. If leadership wants fewer holds, track query turnaround time as a core KPI. It directly impacts DNFB, billing lag, and cash flow. This also ties into broader operational roles like director of coding operations because query discipline is a production lever, not only a quality lever.

Technology can improve query targeting, but it cannot replace judgment. Use tools to surface patterns, then apply human logic to decide if a query is warranted. The industry is already moving in this direction through predictive analytics and automation approaches tied to AI in RCM. If you blindly trust auto prompts, you create high volume low quality queries that burn provider trust.

3: CDI Specificity Terms That Protect You From “Unsupported” Denials

Most CDI wins come from specificity. Not because specificity is “nice,” but because payers deny what they cannot verify. Specificity means documenting the details that separate one code from another. Site, laterality, stage, acuity, cause, and linkage are not optional details when they change code selection. Coders can only code what is written, so CDI exists to make the clinical truth readable and defensible.

Linkage language is one of the biggest hidden problems. Providers may document two conditions in the same note but never link them. A classic example is when a complication is implied but not stated. When documentation does not connect cause and effect, coders cannot assume it. CDI terms like “etiology” and “clinical indicators” exist because payers demand a chain of logic. If you want to train for this mindset, build it alongside specialty coding references like cardiology CPT coding, radiology CPT coding, and emergency medicine CPT codes. Specialty documentation is where specificity errors get expensive fast.

MEAT is the practical filter that prevents problem list inflation. If the record shows monitoring, evaluation, assessment, or treatment of a condition, the condition is active. If it does not, it is often historical context, not an active coded diagnosis. This matters in risk capture and in denial defense. Overcoding conditions with no MEAT support is a direct path to audits, especially in an environment shaped by upcoming regulatory changes and payer intensity.

CDI specificity also matters for ICD evolution. Many teams are building crosswalk awareness and documentation habits that map cleanly to newer systems. If you want to stay current, review structured dictionaries like ICD 11 mental health coding, ICD 11 neurological disorders, and ICD 11 respiratory coding. Those resources reinforce how specificity expectations are only getting tighter.

4: CDI Denial and Audit Terms That Decide Whether You Win Appeals

A denial is not just “nonpayment.” It is a structured argument by the payer that your record failed a requirement. CDI terms exist because they map to denial logic. Clinical validation, DRG validation, POA accuracy, and medical necessity are not theoretical. They are the checklist items reviewers use to approve, deny, or recoup.

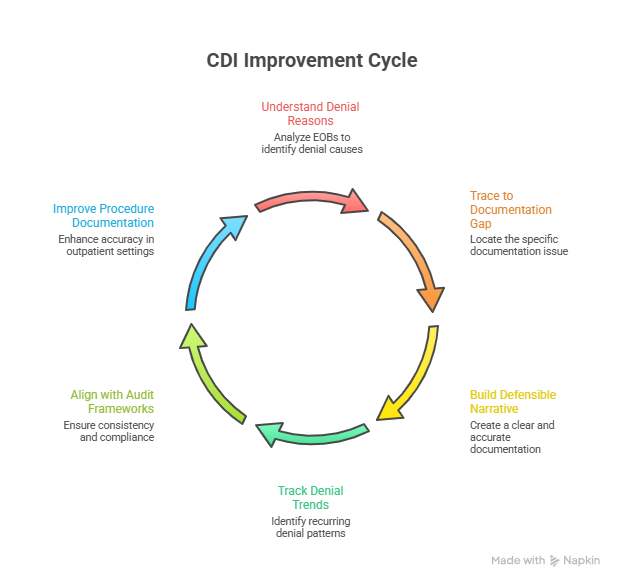

If you want to win denials, you must learn to build a defensible narrative that ties documentation to payer expectations. Start by understanding how payers communicate reasons through an EOB, then trace that reason backward to the exact documentation gap that caused it. Most denial patterns repeat. When teams fail, they treat denials like random events instead of predictable results. That is why denial prevention should be paired with trend tracking like predictive analytics and policy awareness like future Medicare and Medicaid regulations.

Audit defense also depends on consistency. If one note says the patient is stable and another note says severe, reviewers will choose the version that supports denial. Contradictions are not small issues, they are weapons for payers. This is why CDI teams should align with auditing frameworks like medical coding audit terms and compliance frameworks like coding compliance trends. The most profitable claims are often the most reviewed claims, so your documentation must be clean where scrutiny is highest.

Another denial driver is modifiers and procedure documentation in outpatient settings. CDI is not limited to inpatient DRGs. Documentation affects CPT selection, modifier logic, and medical necessity for procedures. If your organization struggles with procedure related denials, sharpen skills using references like gastroenterology CPT codes and the rule focused breakdown in modifier application. CDI is broader than diagnosis, it is the full documentation ecosystem that supports billing.

5: CDI Metrics, Workflow Terms, and Career Language You Need to Grow

CDI careers grow when you can prove impact. That means you need metric language, not just clinical language. Query rate, agreement rate, turnaround time, DRG impact, denial rate, and documentation completeness are not “management talk.” They are the levers that convert CDI work into measurable financial outcomes. If leadership does not see measurable outcomes, CDI becomes a cost center. If leadership sees outcomes, CDI becomes a revenue protection engine.

A strong CDI workflow also ties into long term career paths. Many coders move into CDI because it creates influence over quality and revenue. Others move from CDI into leadership because they understand operations and compliance. If you want that track, study role expectations in director of coding operations and build documentation strength across settings. CDI is one of the cleanest bridges from “production coder” to “systems thinker.”

Technology skills matter more every year, but the value is in validation. You do not get paid for using tools, you get paid for using tools correctly. Learn how automation shifts work by studying how automation will transform billing roles and how coders stay competitive through future skills in the age of AI. The winning CDI professionals use AI to surface gaps, then apply compliant human judgment to close them.

Finally, CDI is affected by regulation pace. If you want to stay employable, track policy updates as part of your weekly routine. Use upcoming regulatory changes and how new healthcare regulations impact coding careers as your guardrails. CDI professionals who understand regulation shifts do not panic when payers change rules. They anticipate, train, and prevent.

6: FAQs, Clinical Documentation Improvement Terms Dictionary

-

A documentation gap means the record is unclear, incomplete, or missing specificity, but the diagnosis might still be true. A clinical validation issue means the diagnosis is documented, but the clinical evidence does not support it. That difference matters because the fix is different. Gaps are solved with compliant queries and specificity, validation issues are solved by aligning the documented diagnosis to clinical indicators or correcting it. For denial defense, combine audit logic from medical coding audit terms with payer outcome reading using an EOB guide.

-

A compliant query is neutral, cites relevant clinical indicators, and allows options including “unable to determine.” A risky query pushes a diagnosis, pushes severity, or frames the answer as predetermined. Risky queries create compliance exposure because they look like upcoding pressure. If your team wants a standard, align query training with coding compliance trends and reimbursement rules like Medicare reimbursement so the query language matches payer expectations.

-

MEAT is a defensible filter that proves a condition is actively addressed, not merely listed. When documentation shows monitoring, evaluation, assessment, or treatment, the condition is clinically active and appropriate for coding when it impacts care. When MEAT is missing, the condition is often historical context, and coding it can create audit exposure. This becomes even more important as payers tighten review behavior under coding compliance trends and future policy shifts like upcoming regulatory changes.

-

Focus on terms that map directly to payer logic: medical necessity, clinical indicators, clinical validation, POA accuracy, DRG validation, and documentation consistency. Denials are usually won by showing the record supports the payer requirement, not by arguing loudly. Train your team to translate denial language using an EOB guide, then build stronger documentation and queries using audit logic from medical coding audit terms.

-

Use AI to find gaps, not to decide diagnoses. Let AI flag missing specificity, contradictions, and mismatched indicators. Then apply human review to validate and query compliantly. The risk appears when teams accept AI suggestions without clinical support, which creates unsupported diagnoses at scale. To stay safe, study AI in revenue cycle management, the future of medical coding with AI, and the skill shift outlined in future skills coders need.

-

The KPIs that matter are the ones tied to outcomes. Query turnaround time impacts billing lag. Agreement rate reflects query quality and provider engagement. Denial rate trends show whether CDI is preventing revenue loss. DRG impact and clinical validation rates show whether documentation is accurate and defensible. If you want to connect CDI work to leadership language, align measurement with operational roles like director of coding operations and revenue logic like Medicare reimbursement.

-

Make it frictionless and targeted. Do not ask for “more detail.” Ask for the exact detail that changes coding or reduces denials, like laterality, stage, acuity, cause, and linkage. Use quick examples from your own denial patterns and show the cost of missing details. Pair training with compliance guidance from coding compliance trends and include the external pressure context from future Medicare and Medicaid billing regulations.