Complete Guide to Electronic Health Record (EHR) Integration Terms

EHR integration is where clean documentation either becomes clean reimbursement—or gets trapped in interfaces, mismatched IDs, and half-mapped data that never makes it into a claim-ready workflow. If you’ve ever watched charges “vanish,” seen denials spike after a go-live, or had leadership blame coding for a systems issue, this guide is built for you. We’ll define the integration terms that actually matter, explain how each one breaks billing in real life, and give you specific actions to reduce revenue leakage, attribution failures, and audit exposure—without drowning you in IT jargon.

1. EHR Integration: The Revenue-Critical Definition

EHR integration isn’t just “systems talking.” It’s the controlled movement of clinical and financial data across workflows so that documentation → coding → billing → payment → reporting stays consistent end-to-end. When integration fails, it usually shows up as “coding problems,” but the root cause is often upstream: missing required elements, broken identity mapping, inconsistent timestamps, or data landing in the wrong field.

The fastest way to diagnose integration risk is to follow a real claim path. Start at the clinical event, trace what the EHR captured, what the interface sent, what the downstream system stored, and what the payer received. That’s where integration terms stop being theoretical and become operational. This is why teams that understand documentation rules (see Medicare documentation requirements for coders) and compliance boundaries (see medical coding regulatory compliance) consistently outperform teams that only know interface names.

Integration also determines whether your org can prove what was captured. If your audit defense depends on screenshots and “trust me,” you’re exposed. Tight integration practices support stronger workpapers, more reliable reporting, and fewer “we can’t reproduce that record” moments—especially when tied to defensible processes like CDI terms and dictionary and consistent note standards like SOAP notes and coding.

EHR Integration Terms Map: What They Mean and What You Must Do (30 Rows)

2. Integration Architectures and Data Exchange Pathways

Most revenue-impacting integration mistakes come from choosing a pathway that doesn’t match the business need. A “quick interface” might move data, but it can also strip context that coders rely on—like onset timing, laterality, procedure intent, or device details. When you see repeated denials that look like “documentation insufficient,” confirm whether the right elements even arrived in the coding/billing system, using frameworks like medical necessity criteria and documentation standards like EMR documentation terms.

Point-to-point interfaces can be fast, but they scale badly. Each new system adds a new “truth.” That’s how organizations end up with five versions of an encounter status and three different “final” flags. The billing team feels it as inconsistent charge release, broken edits, and constant rework—especially when combined with payer-facing complexity like coordination of benefits (COB).

Hub-and-spoke with an integration engine improves governance: you can implement normalization, routing rules, and monitoring in one place. But it also introduces a risk: if you don’t document transformations, the engine becomes a silent policy-maker. That’s why your integration build must be aligned with coding control points like coding edits and modifiers and denial intelligence like CARCs and RARCs—because the engine can create the exact patterns those codes punish.

API-driven integration (FHIR/REST) often wins for real-time workflows, but only if you set governance. Real-time without guardrails becomes “real-time chaos”: duplicate writes, race conditions, and partial updates that make the chart look complete while the claim record is missing critical components. The practical fix is defining a “minimum viable claim dataset” and connecting it to your operations metrics (see revenue cycle metrics and KPIs) and leakage prevention (see revenue leakage prevention).

Finally, understand the difference between message-based and batch pathways. Batch can be fine for analytics, but it’s dangerous for front-end revenue steps. If eligibility or authorization arrives after the visit, your staff will make “best guesses” and your denials will look like “billing errors” when they’re actually “timing architecture errors.” Pair your integration pathway to the operational need, not the vendor’s default.

3. Identity, Attribution, and Master Data Terms That Break Claims

If your leadership has ever asked, “Why are we getting rejected when the care happened and the note is there?”—identity is usually the answer. Integration fails hardest at identity because it’s the only area where a single character can destroy the entire workflow: an extra zero in an MRN, a mismatched NPI, a wrong billing entity, or a coverage order flipped at registration.

Start with patient identity. A Master Patient Index (MPI) is not “an IT thing.” It’s a revenue stabilizer. Duplicate patients split histories, break medical necessity continuity, and undermine risk-based programs. If your chart shows comorbidities but the billing system doesn’t, don’t blame coders first—confirm whether the problem list and diagnoses were merged correctly (see problem lists in medical documentation) and whether documentation concepts were normalized (see CDI dictionary).

Next is provider identity: NPI, taxonomy, rendering vs billing provider, and location. This is where integration can cause “perfectly coded, instantly denied” claims. If an interface maps the attending provider into the rendering field for a service that requires the performing provider, you’ll see payer edits fire repeatedly—and staff will waste hours “fixing coding” when the real fix is master data governance. Tie provider identity controls to compliance requirements (see coding regulatory compliance) and to payer-facing structures like physician fee schedule terms where provider attributes can change allowable payment logic.

Billing entity identity (TIN) is equally brutal. A small mismatch between TIN/NPI enrollment and the entity billed will create rejections that look like “front desk errors” but are actually “integration-to-practice-management mapping” failures. This is why EHR integration teams must understand practice management logic (see practice management systems terms) and clearinghouse realities (see clearinghouse terminology).

Coverage identity adds another layer: subscriber vs patient, group numbers, plan types, and COB ordering. If your EHR captures coverage but the billing system receives a truncated plan identifier, you’ll get “insurance not found” and “coverage inactive” errors that are not solvable by calling the payer. They’re solvable by integration mapping and eligibility feedback loops, anchored in clean revenue-cycle software practices (see RCM software terms).

If you participate in quality/payment models, identity becomes attribution. Programs tied to value-based care punish identity issues because the money moves based on who is credited for care, not just whether the claim went through. That’s why EHR integration vocabulary overlaps directly with value-based care coding terms, MACRA terms, and MIPS. If identity breaks, reporting breaks, and your performance story collapses even if care delivery was strong.

Quick Poll: What is your biggest EHR integration pain right now?

4. Mapping, Transformation, and Interface Build Terms

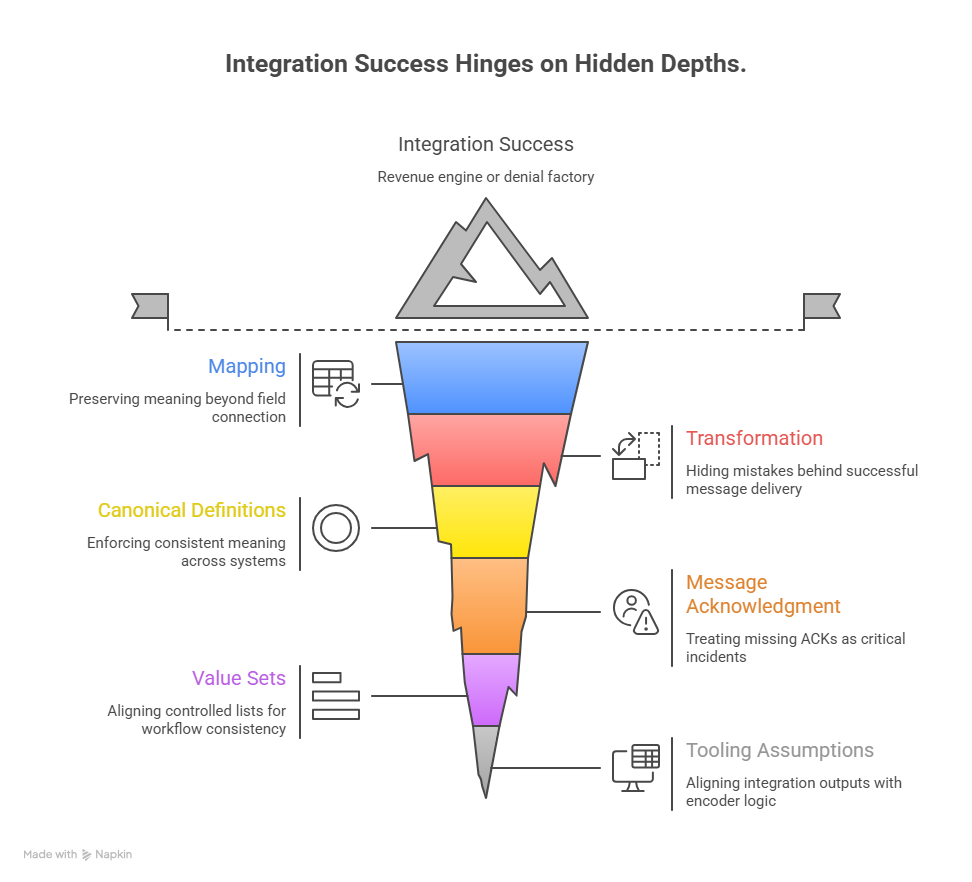

This is where integration becomes either a revenue engine or a denial factory. Mapping is not “connect field A to field B.” Mapping is preserving meaning. If your source has a concept like “present on admission” or “site/laterality,” but the destination only receives a generic label, then your downstream coding workflow loses defensibility—even if the note looks complete. That’s why mapping must align to the documentation concepts coders actually use (see Medicare documentation requirements) and to the operational frameworks your team relies on (see charge capture terms).

Transformation is the most dangerous integration term because it hides mistakes behind “successful” message delivery. Dates get reformatted, timezones convert incorrectly, units shift, and code values get remapped to “closest match.” The interface shows green. Billing shows red. If you’ve ever seen a payer deny for “invalid date of service” or “procedure inconsistent with modifier,” suspect transformation rules first, then confirm against your coding-edit expectations (see coding edits and modifiers).

A high-value integration build uses canonical definitions. That means you define what “encounter start,” “encounter end,” “performing provider,” “billing provider,” “charge posted,” and “charge released” mean across systems, and you enforce that definition in your interfaces. Without canonical definitions, every downstream team invents their own truth, and your analytics become political instead of factual. This is where aligning to RCM KPIs and cost reporting terms becomes crucial: inaccurate upstream integration corrupts financial reporting, not just claims.

Message acknowledgment (ACK) handling is another term that decides whether “sent” means “done.” If your system doesn’t treat missing ACKs as incidents, you’ll build a culture of blind spots: charges missing for days, results not filed, eligibility never posted back. Those blind spots turn into timely filing risk, late coding queues, and “we’re always behind” operations. Tie ACK failures to your denial intelligence workflow using CARCs and RARCs so your team can prove when the cause is systemic rather than staff error.

Integration builds also involve value sets (controlled lists of statuses, types, and codes). When two systems use different status definitions—like “final,” “complete,” “signed,” “posted”—you get workflow deadlocks. Coding waits because the chart looks unsigned, while the clinic thinks it’s done. Billing can’t release because the charge status never flips. Solving this requires governance and documentation discipline—supported by terminology and process standards like medical record retention terms and workflow clarity around query resolution (see coding query process terms).

If your environment uses third-party encoder tools, interface logic can also shape what coders see and what edits fire. That’s why it’s critical to align integration outputs with tooling assumptions (see encoder software terms) and clinical workflow realities (see EMR documentation terms).

5. Testing, Monitoring, and Change Control Terms That Prevent Outages

Most revenue disruptions don’t come from “bad design.” They come from uncontrolled change. An EHR upgrade, a code table refresh, a payer requirement shift, or a vendor patch changes one small field—and suddenly your denials spike and no one can trace what happened. This is why integration vocabulary must include terms like regression testing, reconciliation, monitoring, error queues, and change control—because these are the terms that stop revenue hemorrhage after “minor updates.”

Regression testing means you test the workflows that matter most, not just whether messages arrive. Your “critical path tests” should include: patient registration → coverage posting → eligibility results → encounter creation → charge capture → claim creation → remittance posting. If you only test the interface and not the revenue workflow, you’re testing the wrong thing. Tie your test cases to denial patterns and documentation dependencies using medical necessity criteria and specialty-specific logic when relevant (for example, anesthesia workflows often break on time and status mapping; see anesthesia coding terms).

Reconciliation is the difference between “we think it’s fine” and “we can prove it’s fine.” A high-functioning revenue org runs automated reconciliations that compare source events to destination records. Orders vs charges. Procedures vs claims. Encounters vs bills. Remits vs posted payments. Reconciliation is also how you prove revenue leakage and fix it systematically (see revenue leakage prevention) instead of blaming staff or chasing one-off issues.

Monitoring should be revenue-aware. IT monitoring often focuses on uptime, not business outcome. A feed can be “up” while dropping 12% of messages due to a value-set mismatch. Your monitoring should alert on business thresholds: volume anomalies, spike in error queues, missing ACKs, and time-to-post metrics. Then map those alerts to operational KPIs (see RCM metrics and KPIs) so leadership understands the financial risk in hours, not weeks.

Error queues are not “IT backlog.” They are delayed reimbursement. Every failed message has a downstream cost: delayed charge release, rework, missed timely filing, or payer rejects. The fix is ownership and triage logic: who investigates, how quickly, and what constitutes a root-cause fix. If you treat errors as “normal,” you normalize revenue loss.

Change control is the term that protects you from denial spikes after upgrades. It means: documented change request, defined scope, test evidence, approval, release notes, rollback plan, and post-release validation. This is especially important when changes touch payer-sensitive fields—like provider IDs, location, taxonomy, modifiers, and diagnosis presentation—because those changes directly affect reimbursement logic (see physician fee schedule terms) and reporting for programs like MACRA and MIPS.

Finally, document data lineage: the traceable path from source capture to payer-facing output. Data lineage is your credibility in disputes. When a payer challenges a claim or leadership challenges a denial spike, lineage lets you show exactly where the data changed or dropped. It also improves audit readiness because you can demonstrate consistent controls, not just anecdotal fixes—supported by governance knowledge like regulatory compliance and defensible documentation practices like CDI.

6. FAQs: EHR Integration Terms (High-Value Answers)

-

An interface is a single connection or feed (for example, ADT messages). Integration is the end-to-end system behavior that ensures data remains correct, complete, and usable across workflows. If your interface is “up” but charge capture is incomplete, you have interface success and integration failure—so you must validate via reconciliation (see charge capture terms) and denial patterns like CARCs.

-

Because payers validate enrollment and attribution based on billing entity and provider identity, not narrative notes. A perfect chart can still produce a rejected claim if the billing provider, rendering provider, or entity mapping is wrong—often due to master data mismatch across systems. This is why integration must align to practice management logic (see practice management systems terms) and payer-facing rules (see physician fee schedule terms).

-

It usually means one of three things: (1) a field wasn’t included in the message, (2) the destination rejected the value due to a validation rule, or (3) a transformation/mapping rule routed it incorrectly. The fastest fix is to define a minimum dataset for coding and billing—aligned to Medicare documentation requirements—and then reconcile completeness daily using RCM monitoring tied to RCM KPIs.

-

Use change control + regression testing that validates revenue workflows, not just message flow. Require test evidence on real scenarios: coverage, encounter timing, charge posting, claim creation, and remittance posting. Then monitor post-release outcomes using denial intelligence (see RARCs) and ensure compliance alignment (see coding regulatory compliance).

-

Coders should focus on terms tied to documentation completeness and defensibility: mapping, transformation, encounter integrity, provider identity, problem list consistency, and write-back. If those are unstable, coding becomes “guessing with consequences.” Anchor your coding workflows to standardized documentation structures like SOAP notes and coding and CDI governance via CDI terminology.

-

Run reconciliation that compares clinical source events to posted charges and billed claims. Start with high-volume services and high-denial categories. If services appear in orders/results but not in charges, the issue is likely integration or CDM routing, not coder performance. Use leakage language and prevention frameworks from revenue leakage prevention and tie findings to operational tools like RCM software terms.