Comprehensive Guide to Problem Lists in Medical Documentation

Medical documentation lives or dies on clarity, and the problem list is where clarity gets tested. A messy list doesn’t just confuse care teams—it quietly breaks coding logic, weakens medical necessity, distorts risk, and leaves you defenseless in audits. If your organization treats the problem list like “nice-to-have chart clutter,” you’ll keep paying for it in denials, missed capture, inconsistent quality scores, and provider burnout.

This guide shows how to build a problem list that coders can trust, auditors can’t easily punch holes in, and clinicians won’t hate maintaining—using concrete workflows, decision rules, and compliance-grade evidence habits.

1) Problem Lists: The Hidden Control Center for Coding, Quality, and Compliance

A problem list is not a dumping ground for diagnoses—it’s the index that drives downstream decisions: what belongs on a claim, what must be supported in the note, what affects risk logic, and what quality programs assume is true. When it’s wrong, everything attached to it becomes fragile.

A strong problem list reduces rework because coders stop chasing contradictions across HPI, A/P, and historical diagnoses—especially when your team follows a standardized coding query process to resolve ambiguity instead of guessing. It also tightens medical necessity defensibility because services become traceable to documented clinical need, aligned with the same logic payers use when evaluating medical necessity criteria.

It also impacts risk capture and value-based performance. When chronic conditions live in the list but aren’t validated in the encounter, your chart looks like copy-forward inflation—exactly the kind of pattern that triggers clinical validation disputes and recoupments. That’s why problem list governance must align with risk adjustment coding principles and the real-world documentation expectations baked into value-based care coding programs.

The hard truth: if your chart cannot prove who updated what and why, your organization is vulnerable. Your best defense is traceability—how conditions enter the list, how they’re validated, how they’re retired, and how changes are captured in your coding audit trails. When that traceability exists, CDI stops being a blame game and becomes a clean, evidence-driven process supported by shared terminology like the CDI terms dictionary.

2) What “Counts” as a Problem List Entry: Standards That Survive Denials and Audits

Most problem-list-related denials aren’t about the ICD code itself—they’re about proof. Payers don’t care that a diagnosis exists somewhere in the chart; they care that it’s supported in the encounter, relevant to care, and consistent with the record. If your governance doesn’t match compliance logic, you’ll keep losing fights you should be winning.

Start by aligning your definitions with compliance expectations like those covered in medical coding regulatory compliance, then operationalize them as entry rules.

Use these four “entry gates” as policy:

Clinical validity: Is there defensible evidence—exam findings, labs, imaging, specialist reports, medication indication, or structured assessment? Without it, you’re asking to get hit during financial audits in medical billing.

Current relevance: Is it affecting today’s decision-making—orders, monitoring, counseling, treatment, or risk stratification? If it doesn’t change care, it’s not active.

Specificity: Vague labels (“kidney disease,” “anemia”) create billing ambiguity and reporting chaos; apply the same discipline you use when handling coding edits and modifiers.

Documentation linkage: An “active” problem must appear in the note’s A/P with an action—monitor, evaluate, address, treat—supported by principles from clinical documentation integrity.

One of the most dangerous operational failures is mixing “billing diagnoses” with “clinical history.” If teams start adding diagnoses to “help the claim,” they create patterns that can drift into fraud/waste/abuse exposure—especially when the same behavior repeats at scale, exactly what FWA terminology training is designed to prevent.

Also, don’t ignore record lifecycle rules. If you can’t reliably produce supporting documentation because retention practices are sloppy, you lose even when the care was correct—which is why medical record retention terms should be part of your documentation governance, not an afterthought.

3) The Problem List Workflow That Actually Works: Ownership, Reconciliation, and CDI Without Chaos

If your problem list is a battlefield, it’s usually because no one owns it, reconciliation isn’t standardized, and the EHR encourages copy-forward. Fixing this isn’t “tell providers to do better.” It’s building a workflow where the right behavior is routine.

Step 1: Assign ownership by specialty and setting. Define primary ownership per condition type and make it explicit. Otherwise, coders get blamed for “missing diagnoses” while clinicians assume the list is “someone else’s job.” Treat this as revenue integrity infrastructure the same way you manage charge capture.

Step 2: Build reconciliation into the visit. The closeout should not be optional. Use a routine:

pre-visit: merge duplicates, retire resolved, validate chronic problems

during visit: ensure problems connect to actions

closeout: ensure the note’s assessment matches what will support the claim

This reduces denial volume and makes downstream payer response analysis cleaner through CARCs and RARCs.

Step 3: Use CDI as a precision tool. Define objective triggers: conflicting status, missing specificity, unsupported chronic conditions that affect risk, and mismatch between the list and A/P. When queries are standardized and tracked, they stop being personal and start being operational—supported by a shared language and terminology from medical claims submission terminology.

Step 4: Make the EHR enforce light guardrails. Use controlled vocabulary to prevent three versions of the same condition from destroying reporting. This becomes even more critical if you’re using computer-assisted coding or relying on vendor-driven workflows shaped by coding software terminology—because automation scales whatever you feed it.

And if you’re building AI workflows, remember: AI improves speed, not truth. If the problem list is inconsistent, you’ll scale errors into denial volume, which is exactly why teams should understand AI in revenue cycle trends and how predictive analytics can mislead when source data is messy.

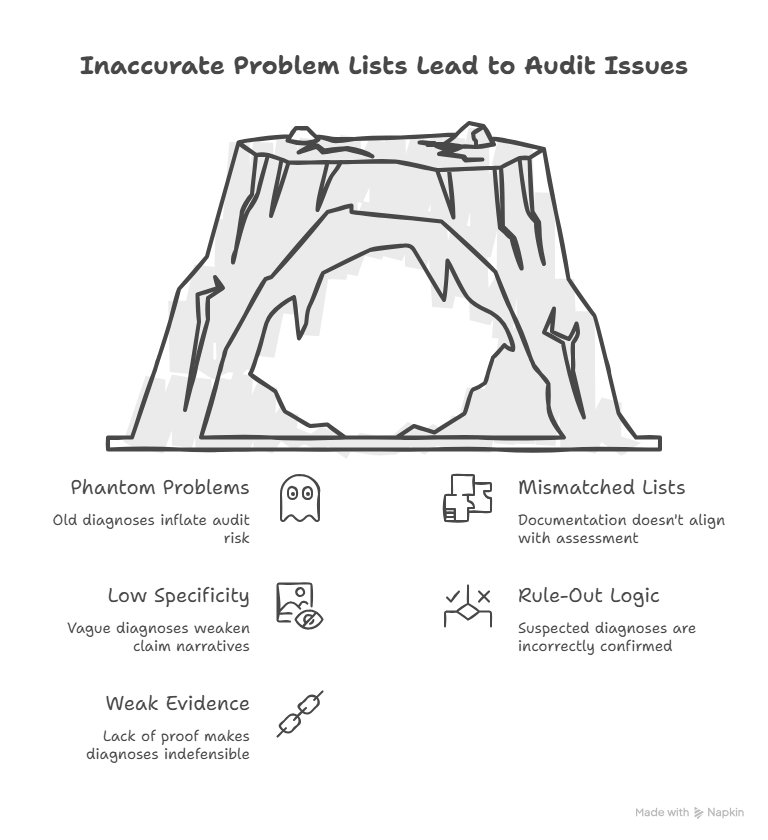

4) The Most Expensive Problem List Errors (and Exactly How to Fix Them)

Error 1: Phantom problems that never get retired. Old diagnoses stay active forever, and they become audit magnets because they look like intentional inflation. Fix it with a retirement rule (resolution date + proof), a hygiene cadence, and a hard stop: problems not validated annually must be re-attested or moved to history. This matters even more in program reporting tied to MACRA and operational performance under MIPS.

Error 2: The list doesn’t match the assessment/plan. If CHF and CKD sit active but the note addresses none of it, your documentation footprint screams copy-forward. Build a closeout checklist: every active problem must have at least one action, and irrelevant conditions must move out of active. This coherence helps when payer complexity increases through coordination rules like coordination of benefits.

Error 3: Low specificity that forces downcoding. If your list allows vague diagnoses, your claim narrative becomes weak. Define “must-have” details and enforce them. If your teams are building readiness for evolving standards like ICD-11 coding best practices, you need this discipline now—not later.

Error 4: Outpatient lists polluted with rule-out logic. Don’t let “suspected” become “confirmed” because someone clicked the wrong option. Document symptoms, document workup, and promote only when confirmed. This is exactly the kind of knowledge that separates average coders from exam-ready coders studying CPC terminology and CCS preparation.

Error 5: Weak evidence habits. Audits don’t just test whether you coded “correctly.” They test whether you can prove the condition was present and relevant. Build evidence habits that make your story defensible. Also validate that your submission pipeline won’t distort your diagnosis logic—especially if you rely on a vendor, which is why clearinghouse terminology matters.

5) Turning the Problem List Into a Revenue-Protecting System: Metrics, Controls, and Audit Defense

Once workflows are stable, you need controls—otherwise the list slowly degrades.

Track:

% of active problems with same-visit A/P linkage

% of chronic problems with annual validation

duplicate rate

unspecified diagnosis rate

retirement lag (resolved but still active)

These metrics belong in leadership reporting the same way denial and leakage metrics do, which aligns naturally with revenue cycle KPIs and ongoing revenue leakage prevention programs.

Audit defense also depends on your ability to trace issues through payer outcomes and cash impact, so teams should connect documentation integrity to accounts receivable performance and reimbursement-related reporting.

If you’re operating in shared-risk ecosystems, accurate condition lists matter beyond claims. Attribution, quality performance, and population documentation also interact with structures defined in ACO billing terms, where “sloppy lists” can become “sloppy performance.”

6) FAQs: Problem Lists in Medical Documentation

-

Coders can recommend updates, but governance must define who owns clinical truth. The safest model is standardized queries and provider validation, supported by consistent definitions like those in AMBCI’s home health coding terms dictionary.

-

Use an annual validation rule for chronic conditions and a retirement policy for items not addressed. Then audit the “copied but not supported” pattern and coach specifically, reinforcing process discipline through quality assurance in medical coding.

-

At minimum, the note must show the condition is clinically relevant and includes an action (monitor/evaluate/address/treat). Stronger evidence habits reduce clinical validation disputes and improve denial resilience.

-

Clean, accurate problems strengthen the alignment between documented complexity and billed services. If the assessment truly matches active problems, your coding story becomes more consistent with reimbursement logic discussed in physician fee schedule terminology.

-

Use specialty ownership rules and strict evidence expectations for services that get audited heavily, especially in workflows tied to dialysis documentation and coding and infusion and injection therapy billing.

-

Use validation workflow: compare evidence, reconcile terminology, and document the resolution. Your goal is one defensible story, not competing narratives.

-

Standardize entry templates, require statuses, and enforce quick retirement rules. High-volume settings need guardrails that reduce duplicates and keep the list defensible, similar to process discipline in ambulance and emergency transport coding.

-

Track denial patterns, unspecified diagnosis rates, duplicates, and audit outcomes. Tie improvements to financial reporting so leadership sees it as revenue protection, including impacts visible in cost reporting.